“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Friday 16 February 2024

Wednesday 30 August 2023

Tuesday 25 July 2023

A Level Economics: Practice Questions on Supply-side Policies

MCQs

Supply side policies aim to improve the productive capacity of an economy by: a) Increasing government spending b) Controlling inflation c) Boosting aggregate demand d) Enhancing the quantity and quality of factors of production Solution: d) Enhancing the quantity and quality of factors of production

Which of the following is an example of a supply side policy? a) Increasing government welfare programs b) Reducing interest rates c) Increasing taxes on luxury goods d) Promoting investment in human capital through education and training Solution: d) Promoting investment in human capital through education and training

Supply side policies can lead to long-term economic growth by: a) Increasing short-term aggregate demand b) Reducing taxes for the wealthy c) Expanding the economy's productive potential d) Encouraging imports over exports Solution: c) Expanding the economy's productive potential

How do supply side policies differ from demand side policies? a) Supply side policies focus on increasing government spending, while demand side policies focus on reducing taxes. b) Supply side policies aim to increase the quantity and quality of factors of production, while demand side policies focus on influencing aggregate demand. c) Supply side policies aim to control inflation, while demand side policies aim to reduce unemployment. d) Supply side policies are only relevant during economic recessions, while demand side policies are applicable during economic expansions. Solution: b) Supply side policies aim to increase the quantity and quality of factors of production, while demand side policies focus on influencing aggregate demand.

Which of the following is a limitation of supply side policies? a) They can lead to high inflation. b) They may cause a decline in aggregate demand. c) They may exacerbate income inequality. d) They are only effective in the short run. Solution: c) They may exacerbate income inequality.

A country's supply side policies include reducing regulations, investing in infrastructure, and promoting research and development. Which of the following is a likely outcome of these policies? a) Increased government budget deficit b) Reduced economic growth c) Higher productivity and innovation d) Increased trade barriers Solution: c) Higher productivity and innovation

The "Marshall Lerner condition" states that a currency depreciation will improve the trade balance if: a) The sum of the price elasticities of demand for exports and imports is greater than one. b) The sum of the price elasticities of demand for exports and imports is equal to one. c) The sum of the price elasticities of demand for exports and imports is less than one. d) The sum of the price elasticities of demand for exports and imports is negative. Solution: a) The sum of the price elasticities of demand for exports and imports is greater than one.

The "J curve effect" refers to: a) The long-term improvement of trade balance after a currency depreciation. b) The immediate improvement of trade balance after a currency depreciation. c) The short-term worsening of trade balance after a currency depreciation. d) The immediate improvement of trade balance after a currency appreciation. Solution: c) The short-term worsening of trade balance after a currency depreciation.

How do supply side policies impact a country's production possibilities frontier (PPF)? a) They cause the PPF to shift inward, indicating reduced production capacity. b) They have no effect on the PPF. c) They shift the PPF outward, indicating increased production capacity. d) They cause the PPF to become a straight line instead of a curve. Solution: c) They shift the PPF outward, indicating increased production capacity.

Which of the following is an advantage of holding exchange rates artificially low? a) Reduced export competitiveness b) Improved export competitiveness c) Increased imports and trade deficits d) Higher interest rates Solution: b) Improved export competitiveness

Analyze the historical context and economic challenges that led to the prominence of supply side policies during the 1980s in the United States and the United Kingdom, and evaluate the long-term impact of "Reaganomics" and "Thatcherism" on their respective economies.

Evaluate the effectiveness of supply side policies in promoting economic growth and addressing income inequality, considering their impact on factors such as labor market reforms, investment in human and physical capital, and research and development incentives.

Analyze the advantages and disadvantages of artificially managing exchange rates to improve export competitiveness. Assess the potential risks associated with holding exchange rates artificially low and its impact on inflation, import costs, and speculative activities.

Discuss the concept of the "Marshall Lerner condition" and the "J curve effect" concerning exchange rate changes. Evaluate their relevance and implications for trade balances and the overall economic stability of a country.

Considering the impact of supply side policies on the production possibilities frontier (PPF), aggregate demand (AD), and aggregate supply (AS), compare and contrast the effectiveness of supply side measures with demand side policies in achieving long-term economic growth and stability. Analyze their respective limitations and potential trade-offs.

Wednesday 21 June 2023

Luck and Politics

Monday june 19th was a typical day in British politics insofar as it involved a series of humiliations for the Conservative Party. mps approved a report on Boris Johnson condemning the former prime minister for lying to Parliament over lockdown-busting parties. Rishi Sunak skipped proceedings for a fortunately timed meeting with Sweden’s prime minister. On the same day, the invite emerged for an illegal “Jingle and Mingle” event at the party’s headquarters during the Christmas lockdown of 2020. A video of the event had already circulated, with one staffer overheard saying it was fine “as long as we don’t stream that we’re, like, bending the rules”. Labour, through no efforts of their own, had their reputation comparatively enhanced.

Luck is an overlooked part of politics. It is in the interests of both politicians and those who write about them to pretend it plays little role. Yet, as much as strategy or skill, luck determines success. “Fortune is the mistress of one half of our actions, and yet leaves the control of the other half, or a little less, to ourselves,” wrote Machiavelli in “The Prince” in the 16th century. Some polls give Labour a 20-point lead. Partly this is because, under Sir Keir Starmer, they have jettisoned the baggage of the Jeremy Corbyn-era and painted a picture of unthreatening economic diligence. Mainly it is because they are damned lucky.

If Sir Keir does have a magic lamp, it has been buffed to a blinding sheen. After all, it is not just the behaviour of Mr Johnson that helps Labour. Britain is suffering from a bout of economic pain in a way that particularly hurts middle-class mortgage holders, who are crucial marginal voters. Even the timing helps. Rather than a single hit, the pain will be spread out until 2024, when the general election comes due. Each quarter next year, about 350,000 households will re-mortgage and become, on average, almost £3,000 ($3,830) per year worse off, according to the Resolution Foundation. Labour strategists could barely dream of a more helpful backdrop.

Political problems that once looked intractable for Labour have solved themselves. Scotland was supposed to be a Gordian knot. How could a unionist party such as Labour tempt left-wing voters of the nationalist Scottish National Party (snp)? The police have fixed that. Nicola Sturgeon, the most talented Scottish politician of her generation, found herself arrested and quizzed over an illicit £100,000 camper van and other matters to do with party funds. The snp’s poll rating has collapsed and another 25 seats are set to fall into the Labour leader’s lap thanks to pc McPlod and (at best) erratic book-keeping by the snp.

It is not the first time police have come to Sir Keir’s aid. He promised to quit in 2022 if police fined him for having a curry and beer with campaigners during lockdown-affected local elections in 2021. Labour’s advisers were adamant no rules were broken. But police forces were erratic in dishing out penalties, veering between lax and draconian. It was a risk. Sir Keir gambled and won.

Luck will always play a large role in a first-past-the-post system that generates big changes in electoral outcomes from small shifts in voting. Margins are often tiny. Mr Corbyn came, according to one very optimistic analysis, within 2,227 votes of scraping a majority in the 2017 general election, if they had fallen in the right places. Likewise, in 2021, Labour faced a by-election in Batley and Spen, in Yorkshire. A defeat would almost certainly have triggered a leadership challenge; Labour clung on, narrowly, and so did Sir Keir. If he enters Downing Street in 2024, he will have 323 voters just outside Leeds to thank.

Sir Keir is hardly the first leader to benefit from fortune’s favour. Good ones have always needed it. Sir Tony Blair reshaped Labour and won three general elections. But he only had the job because John Smith, his predecessor, dropped dead at 55. (“He’s fat, he’s 53, he’s had a heart attack and he’s taking on a stress-loaded job” the Sun had previously written, with unkind foresight.) Without the Falklands War in 1982, Margaret Thatcher would have asked for re-election soon afterwards based on a few years of a faltering experiment with monetarism. Formidable political talent is nothing without a dash of luck.

Often the most consequential politicians are the luckiest. Nigel Farage has a good claim to be the most influential politician of the past 20 years. He should also be dead. The former leader of the uk Independence Party was run over in 1985. Then, in 1987, testicular cancer nearly killed him. In 2010, he survived a plane crash after a banner—“Vote for your country—Vote ukip”—became tangled around the plane. Smaller factors also played in Mr Farage’s favour: when he was a member of the European Parliament he was randomly allocated a seat next to the European Commission president, providing a perfect backdrop for viral speeches. (“They handed me the internet on a plate!” chortles Mr Farage.) Britain left the eu, in part, because Mr Farage is lucky.

Stop polishing that lamp, you’ll go blind

Too much good luck can be a bad thing. David Cameron gambled three times on referendums (on the country’s voting system, on Scottish independence and on Brexit). He won two heavily and lost one narrowly. Two out of three ain’t bad, but it is enough to condemn him as one of the worst prime ministers on record. “A Prince who rests wholly on fortune is ruined when she changes,” wrote Machivelli. It was right in 1516; it was right in 2016. Labour would do well to heed the lesson. It sometimes comes across as a party that expects the Conservatives to lose, rather than one thinking how best to win.

Fortune has left Labour in a commanding position. Arguments against a Labour majority rely on hope (perhaps inflation will come down sharply) not expectation. Good luck may power Labour to victory in 2024, but it will not help them govern. The last time Labour replaced the Conservatives, in 1997, the economy was flying. Now, debt is over 100% of gdp. Growth prospects are lacking, while public services are failing. It will be a horrible time to run the country. Bad luck.

Wednesday 14 June 2023

Saturday 5 December 2020

Thatcher or Anna moment? Why Modi’s choice on farmers’ protest will shape future politics

Has the farmers’ blockade of Delhi brought Narendra Modi to his Thatcher moment or Anna moment? It is up to Modi to answer that question as India waits. It will write the course of India’s political economy, even electoral politics, in years to come.

For clarity, a Thatcher moment would mean when a big, audacious and risky push for reform, that threatens established structures and entrenched vested interests, brings an avalanche of opposition. That is what Margaret Thatcher faced with her radical shift to the economic Right. She locked horns with it, won, and became the Iron Lady. If she had given in under pressure, she’d just be a forgettable footnote in world history.

--Also watch

Anna moment is easier to understand. It is more recent. It was also located in Delhi. Unlike Thatcher who fought and crushed the unions and the British Left, Manmohan Singh and his UPA gave in to Anna Hazare, holding a special Parliament session, going down to him on their knees, implicitly owning up to all big corruption charges. Singh ceded all moral authority and political capital.

By the time Anna returned victorious for the usual rest & recreation at the Jindal fat farm in Bangalore, the Manmohan Singh government’s goose had been cooked. Anna was victorious not because he got the Lokpal Bill. Because that isn’t what he and his ‘managers’ were after. Their mission was to destroy UPA-2. They succeeded. Of course, helped along by the spinelessness as well as guilelessness of the UPA.

Modi and his counsels would do well to look at both instances with contrasting outcomes as they confront the biggest challenge in their six-and-a-half years. Don’t compare it with the anti-CAA movement. That suited the BJP politically by deepening polarisation; this one does the opposite. It’s a cruel thing to say, but you can’t politically make “Muslims” out of the Sikhs.

That “Khalistani hand” nonsense was tried, and it bombed. It was as much of a misstep as leaders of the Congress calling Anna Hazare “steeped in corruption, head to toe”. Remember that principle in marketing — nothing fails more spectacularly than an obvious lie. As this Khalistan slur was.

The anti-CAA movement involved Muslims and some Leftist intellectual groups. You could easily isolate and even physically crush them. We are merely stating a political reality. The Modi government did not even see the need to invite them for talks. With the farmers, the response has been different.

Besides, this crisis has come on top of multiple others that are defying resolution. The Chinese are not about to end their dharna in Ladakh, the virus is raging and the economy, downhill for six quarters, has been in a free fall lately. Because politically, economically, strategically and morally the space is now so limited, this becomes the Modi government’s biggest challenge.

Also read: Shambles over farmers’ protest shows Modi-Shah BJP needs a Punjab tutorial

Modi has a complaint that he is given too little credit as an economic reformer. That he has brought in the bankruptcy law, GST, PSU bank consolidation, FDI relaxations and so on, but still too many people, especially the most respected economists, do not see him as a reformer.

There is no denying that he has done some political heavy lifting with these reformist steps. But some, especially GST, have lost their way because of poor groundwork and execution. And certainly, all that the sudden demonetisation did was to break the economy’s momentum. His legacy, so far, is of slowing down and then reversing India’s growth.

Having inherited an economy where 8 per cent growth was the new normal, now RBI says it will be 8 per cent, but in the negative. It isn’t the record anybody wanted in his seventh year, with India’s per capita GDP set to fall below Bangladesh’s, according to an October IMF estimate.

The pandemic brought Modi the “don’t waste a crisis” opportunity. If Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh with a minority government could use the economic crisis of 1991 to carve out a good place for themselves in India’s economic history, why couldn’t he now? That is how a bunch of audacious moves were announced in a kind of pandemic package. The farm reform laws are among the most spectacular of these. Followed by labour laws.

This is comparable now to the change Margaret Thatcher had dared to bring. She wasn’t dealing with multiple other crises like Modi now, but then she also did not have the kind of almost total sway that Modi has over national politics. Any big change causes fear and protests. But this is at a scale that concerns 60 per cent of our population, connected with farming in different ways. That he and his government could have done a better job of selling it to the farmers is a fact, but that is in the past.

The Anna movement has greater parallels, physically and visually, with the current situation. Like India Against Corruption, the farmers’ protest also positions itself in the non-political space, denying its platform to any politician. Leading lights of popular culture are speaking and singing for it. Again, there is widespread popular sympathy as farmers are seen as virtuous, and victims. Just like the activists. Its supporters are using social media just as brilliantly as Anna’s.

Also read: How protesting farmers have kept politicians out of their agitation for over 2 months

There are some differences too. Unlike UPA-2, this prime minister is his own master. He doesn’t need to defer to someone in another Lutyens’ bungalow. He has personal popularity enormously higher than Manmohan Singh’s, great facility with words and a record of consistently winning elections for his party.

But this farmers’ stir looks ugly for him. His politics is built so centrally on the pillar of “messaging” that pictures of salt-of-the-earth farmers with weather-beaten faces, cooking and sharing ‘langars’, offering these to all comers, then refusing government hospitality at the talks and eating their own food brought from the gurdwara while sitting on the floor, and the widespread derision of the “Khalistani” charge is just the kind of messaging he doesn’t want. In his and his party’s scheme of things, the message is the politics.

Thatcher had no such issues, and Manmohan Singh had no chips to play with. How does Modi deal with this now? The temptation to retreat will be great. You can defer, withdraw the bills, send them to the select committee, embrace the farmers and buy time. It isn’t as if the Modi-Shah BJP doesn’t know how to retreat. It did so on the equally bold land acquisition bill, reeling under the ‘suit-boot ki sarkar’ punch. So, what about another ‘tactical retreat’?

It will be a disaster, and worse than Manmohan Singh’s to the Anna movement. At the heart of Modi’s political brand proposition is a ‘strong’ government. It was early days when he retreated on the land acquisition bill. The lack of a Rajya Sabha majority was an alibi. Another retreat now will shatter that ‘strongman’ image. The opposition will finally see him as fallible.

At the same time, farmers blockading the capital makes for really bad pictures. These aren’t nutcases of ‘Occupy Wall Street’. Farmers are at the heart of India. Plus, they have the time. Anybody with elementary familiarity with farming knows that once wheat and mustard, which is most of the rabi crop in the north, is planted, there isn’t that much to do until early April.

You can’t evict them as in the many Shaheen Baghs, and you can’t let them hang on. Even a part surrender will finish your authority. Because then protesters against labour reform will block the capital. That’s why how Modi answers this Thatcher or Anna moment question will determine national politics going ahead. Our wish, of course, is that he will choose Thatcher over Anna. It will be a tragedy if even Modi were to lose his nerve over his boldest reforms.

Wednesday 25 October 2017

The Nature of Money, Modern Money and Bitcoin

Friday 7 October 2016

Thank God Theresa May is continuing the historic Tory tradition of fighting the elite

Whenever an elite is unjust, anywhere in the world, from South Africa to Chile to Saudi Arabia, it’s been the Conservative Party that has bravely fought them by selling them weapons and inviting their leaders to dinner.

Mark Steel in The Independent

What a welcome message from Theresa May, that she’s sick of the elite. The Cabinet all applauded, as you’d expect; although 27 of them are millionaires, that doesn’t make them elite – they all got their money by winning it on scratch cards.

The Prime Minister was only abiding by a change to international law that states everyone who makes a public speech now has to insist they can’t stand the “elite”. Donald Trump – a man whose background is so modest that, in one of his castles, he has to go outside to use the moat – hates the elite. Iain Duncan Smith with his modest 15-up 15-down Tudor mansion is fed up with the elite, too. Boris Johnson stands up against the elite, because his background was so humble that one of the kids at his primary school had an imaginary friend who didn’t have his own valet.

This year, the Queen will probably start her Christmas speech by saying, “My husband and I are sick to death of the elite. When one has been required to reign as a working-class monarch, one rather views these elite types with sufficient disdain to get the right hump.”

But May was more specific. She singled out the “Liberal Metropolitan Elite,” for ruining our lives.

You can understand why, because these are the very people who have spoilt everything with their liberal ways. There’s Topshop’s Philip Green, who wasted millions so he could complete a course as a human rights lawyer and get his hipster beard trimmed. Mike Ashley, condemned for his treatment of staff at Sports Direct, has “homeopath” written all over him.

There’s Alan “cycle lane” Sugar, who, if I remember right, turned down his knighthood as a protest against the number of toads that get run over. And the most powerful man in the media is Rupert Murdoch, who publishes newspapers full of feminism and media studies.

One way we must stop these liberals, she insisted, is prevent human rights lawyers from haranguing the army. She’s right there: if there’s one area in which human rights lawyers have absolutelyno need to investigate, it’s war. Whoever heard of an army that isn’t careful to look after human rights? They should concern themselves with real human rights culprits, such as florists.

These abuses have come about because, for 35 years, British life has been relentlessly liberal. It started with Margaret Thatcher, who shut down the mines so they could be replaced by documentaries on BBC4 about Tibetan dance. And she brought in the Poll Tax, but only because she was convinced this would lead to wider ownership of African wood carvings bought from antique shops in Notting Hill.

Then we had liberal Tony Blair with his liberal invasion of Iraq, in which he insisted the air force only used Fairtrade depleted uranium. Now, at last, we’re all sick of being ruled by these elite liberals.

Conservative figures such as Amber Rudd have this week been forced to ask “can we at last talk about immigration?” Thanks to the elite, who can think of a single occasion in the last six months when anyone in public eye has mentioned immigration?

There are some programmes on radio or television that simply refuse to discuss the issue. For example, during a first-round clash in the Swedish open snooker championship on Eurosport, a whole four minutes went by on the commentary without mention of how you can’t move in Lincolnshire for Bulgarians. And two minutes passed by without any talk of immigration during the two-minute silence on Remembrance Day at the Cenotaph. And if we can’t talk about protecting our borders at that time when can we discuss it?

The idea that we should welcome immigration is a perfect example of how the Liberal Metropolitan Elite operates, because foreigners are alright for some with their cheap nannies but down-to-earth types, bless them, can’t stand people who have the nerve to move over here and fix radiators or bed-bath the elderly.

This week is the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Cable Street, when thousands of people assembled in East London to prevent the British Union of Fascists from marching through a Jewish area. I wonder who was in the crowds that day, linking arms to defy the supporters of Hitler? It can’t have been the working class, since they must all have said “it’s alright for the elite, but these Jews come over here and lower our wages.” So it must have been the Liberal Metropolitan Elite who took on the fascists, by hurling antique carriage clocks at them after distracting them with an avant-garde contemporary dance evening.

Theresa May seems ambitious, because she said she’s going to battle an “international elite”. So they’re global, these elites, and they can only be fought by determined earthy salt-of-the-earth types such as Anna Soubry. Jeremy Hunt, for example, looks exactly like someone who’s just come off an eight-hour shift driving a forklift truck carrying tomatoes round a warehouse for Lidl, shouting “there you go sweetheart, stack them up while I sort out these elite doctors giving it all that about weekends”.

If there’s one thing we know about the Conservative Party, it’s the natural home for common folk who want to take on the international elite.

Whenever an elite is unjust, anywhere in the world, from apartheid South Africa to military Chile or patriarchal Saudi Arabia, it’s been the Conservative Party that has bravely fought them by selling them weapons and inviting their leaders to dinner. Just like the poor-but-happy folk down any council estate always keep a door open for a military dictator, the little darlings.

Sunday 26 June 2016

How Corbyn could checkmate Farage and Johnson's Brexit plans

In the progressive half of British politics we need a plan to put our stamp on the Brexit result – and fast.

We must prevent the Conservative right using the Brexit negotiations to reshape Britain into a rule-free space for corporations; we need to take control of the process whereby the rights of the citizen are redefined against those of a newly sovereign state.

Above all we need to provide certainty and solidarity to the millions of EU migrants who feel like the Brits threw them under a bus this week.

In short, we can and must fight to place social justice and democracy at the heart of the Brexit negotiations. I call this ProgrExit – progressive exit. It can be done, but only if all the progressive parties of Britain set aside some of what divides them and unite around a common objective.

The position of Labour is pivotal. Only Labour can provide the framework of a government that could stop Boris Johnson, abetted by Nigel Farage, turning Britain into a Thatcherite free-market wasteland.

Labour – and I mean here the 400,000 people with party cards and a meeting to go to – must go beyond the analysis and grieving stage, and do something new.

First, Labour must clearly accept Brexit. There can be no second referendum, no legal sabotage effort. Labour has to become a party designed to deliver social justice outside the EU. It should, for the foreseeable future, abandon the objective of a return to EU membership. We are out, and must make the best of it.

Next, we should fight for an early election. Almost all parts of the Labour movement have reason to resist this: for the Blairites it holds the danger that Corbyn will become PM – something they thought they had years to sabotage. For Corbyn, the nightmare is he gets stuck as a Labour prime minister with a Parliamentary Labour Party that does not support him. For the unions, they are out of cash. For the new breed of post-2015 activists, bruised by being told to eff off by what they assumed were their core supporters, it feels like a bad time to go back on the doorstep. But we must go there.

An early election – I favour late November – is the only democratic outcome in the present situation. No politician has a mandate to design a specific Brexit negotiation stance now. The only one with a democratic mandate to rule Britain just resigned, and his party’s 2015 manifesto is junk.

Europe cannot conduct meaningful Brexit negotiations with a scratch-together rump Tory government. So the whole process will be on hold.

In the election Labour should offer an informal electoral pact to the Scottish National Party, Greens and Plaid Cymru. The aims should be a) defeating Ukip and b) preventing the formation of a Tory-Ukip-DUP government that would enact the ultra-right Brexit scenario.

Caroline Lucas has indicated the price of such a pact might be a commitment to proportional representation. Labour – which cannot govern what is left of the UK alone, once Scotland leaves – should accede to this.

If, as a result of the snap election, Labour can form a coalition government with the SNP, Plaid and Greens, it should do so.

However, the most obvious problem is the position of Scotland. Nicola Sturgeon is right to demand a new independence vote, and to explore how to time that vote in a way that maintains Scotland’s continuous membership of the EU.

Given the strength of the remain vote in Scotland, Scottish Labour is faced with a big decision: does it oppose independence and go with Brexit to maintain the Union, or switch now to promoting independence to stay in the EU? I favour the latter, but it should be for Scottish Labour members to make that decision independently.

At Westminster, however, Labour should offer – in return for a coalition government – a no-penalty Scottish secession plan from the UK, funded and overseen by the Treasury and Bank of England.

Proportional representation, coalition government and Scottish independence were not in Labour’s game plan at 10pm on Thursday night. But neither was Brexit.

If the political ideas in your head, cultivated over a lifetime, rebel against all this, you must get used to it: with or without the help of the PLP, Scotland is headed out of the UK. But Labour has the opportunity to make that separation amicable; it will be obligatory for all progressive parties to ally with the Scots as – inevitably – the authoritarians of Ukip try to prevent Sturgeon’s second referendum.

As to what a Labour/SNP/Plaid and Green coalition would argue in the Brexit negotiations, the baseline has to be maintaining the existing progressive legislation on employment, consumer rights, women’s rights, the environment etc. But at the same time a Labour-led Brexit negotiation would have to drive a hard bargain over ending bans on state aid, or on nationalisation.

If it were possible to conclude a deal within the European Economic Area I would favour that. But the baseline has to be a new policy on migration designed for the moment free movement ceases to apply. It should be humane, generous, and led by the needs of employers, local communities and universities – and being an EU member should get you a lot of points.

But – and this is the final mindset shift we in Labour must make – free movement is over. Free movement was a core principle of the EU, developed over time. We are no longer part of that, and to reconnect with our voting base – I don’t mean the racists but the thousands of ordinary Labour voters, including black and Asian people – we have to design a migration policy that works for them, and not for rip-off construction bosses or slavedrivers on the farms of East Anglia.

Britain is not, as the far left peevishly dubbed it, “rainy, fascist island”: we’ve snatched glory from the jaws of ignominy in our history before now – but only when politicians have shown vision.

If they don’t show vision, we – the rank and file of Labour, the left nationalists and the Greens – who have way more in common than political labels suggest, should force them to unite and fight.

Tuesday 8 March 2016

Why the Tory project is bust

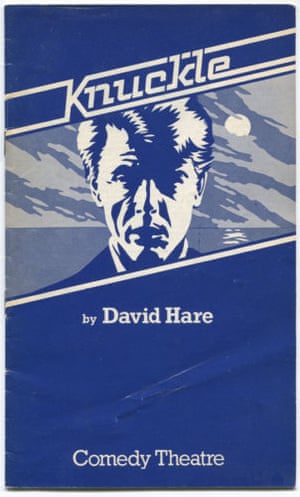

Just over 40 years ago, I wrote a play called Knuckle which tried out for two weeks at the Oxford Playhouse, before going on to open in the West End. It was my fourth full-length play, and one that suffered an extremely difficult birth. I was 26. If only I had known it, its reception was to have a decisive and lasting effect on my life. Knuckle was produced at a time of bitter and fundamental industrial disputes, so the hotel I stayed in along from the theatre was subject to blackouts. It was February and it was freezing cold, and there were evenings when the hotel was lit only by candles placed on the stairs and in my room.

Edward Heath, a Conservative prime minister, was about to announce a markedly unwise election based around the question of “Who runs Britain?” He was tired, he said, of the trade unions having too much power and he wanted to settle the arguments between government and workers once and for all. At the end of February 1974, the electorate gave him a dusty answer – it is always said to be a mistake to go to the people with a question they expect you to answer for yourself – but Heath hung on for a few undignified days in Downing Street, trying to cobble together a coalition, before gracelessly accepting the inevitable. Harold Wilson, the victor, quickly settled with the miners, and the lights came back on again.

The past is comparatively safe, next to the present, because we know how at least one of them turns out. Or do we? One of my purposes last year in publishing a memoir, The Blue Touch Paper, was to reclaim the 1970s from the image that politicians of one fierce bent have successfully imposed with the help of largely compliant historians. The now-familiar version of our island story is that we all spent the 1970s in industrial chaos, with successive governments failing to confront the overbearing unions, until Margaret Thatcher arrived and set about deregulating markets, privatising public assets and generally encouraging citizens to work only for ourselves and our own self-interest. This, we have been continually told over three decades of sustained propaganda, was wholly to the good. The country we now live in with all its crazy excesses of inequality and flagrant immorality in the workplace – bosses in large firms averaging 160 times the salaries of their worst-off employees – is said to be far superior to how it was in the days when labour still held management in some kind of check.

History belongs to the victors. Conservatives in Britain now command not just the economy but the narrative as well, and three recent Labour governments have done little to challenge it. But it is not the case that everything was in chaos until 1979, since when everything has been bliss. The 1970s were disputatious times, times of profound and often bitter argument. Living through them was not easy, and a lot of us suffered wounds that took years to heal. But the political discussions we were having – in particular about how the wishes of working-class employees could be more creatively taken into account – were about important things, things that, disastrously, present-day politicians disdain to address. The shocking rancour of the 1970s now looks like a symptom of their vitality. Today’s quiescence seems more like a phenomenon of resignation than of contentment.

Knuckle was a youthful pastiche of an American thriller, relocating the myth of the hard-boiled private eye incongruously into the home counties. Curly Delafield, a young arms dealer, returns to Guildford in order to try and find his sister Sarah who has disappeared. But in the process he finds himself freshly infuriated by the civilised hypocrisy of his father Patrick Delafield, a stockbroker of the old school. In the play father and son represent two contrasting strands in conservatism. Patrick, the father, is cultured, quiet and responsible. Curly, the son, is aggressive, buccaneering and loud. One of them sees the creation of wealth as a mature duty to be discharged for the benefit of the whole community, with the aim of perpetuating a way of life that has its own distinctive character and tradition. But the other character, based on various criminal or near-criminal racketeers who were beginning to play a more prominent role in British finance in the 1970s, sees such thinking as outdated. Curly’s own preference is to make as much money as he can in as many fields as he can and then to get out fast.

The first thing to notice about my play is that it was written in 1973. Margaret Thatcher was not elected until six years later. So whatever the impact of her arrival at the end of decade, it would be wrong to say that she brought anything very new to a Tory schism that had been latent for years. Surely, she showed power and conviction in advancing the cause of the Curly Delafield version of capitalism – no good Samaritan could operate, she once argued, unless the Samaritan were filthy rich in the first place. How else to explain the fact that the very split that she formally confronted in the different mindsets within her government – she named the two opposing sides “wets” and “drys” – was explored in my work at the Oxford Playhouse more than five years before? In 1951, resolving never to vote for them again, the novelist Evelyn Waugh had complained that the Conservative party in his lifetime “had never put the clock back a single second”. But the administrations that Thatcher first led and then inspired have never shown interest in conserving anything at all. The giveaway, for once, has not been in the name.

You may say that the party aims, like all such parties, to keep the well off well off. That, never forget, is any rightwing grouping’s conservative mission, which will offer a blindingly simple explanation for the larger part of its behaviour. And for obvious reasons, the money party in this particular culture has also aimed to perpetuate the narcotic influence of the monarchy. But with these two exceptions, it is hard to think of any area of public activity – education, justice, defence, health, culture – which any of the last seven Conservative governments have been interested in protecting, let alone conserving. On the contrary, they have preferred a state of near‑Maoist revolution, complaining that, in an extraordinary coincidence, almost every aspect of British life except retail and finance is incompetently organised. Who could have imagined it? And after all those dominant Conservative governments! In this belief, they have launched waves of attacks against teachers, doctors, nurses, policemen and women, soldiers, social workers, civil servants, local councillors, firefighters, broadcasters and transport workers – all of whom they openly scorn for the mortal sin of not being financiers or entrepreneurs.

For a party that is meant to like people, and to believe in enabling them, the modern Conservative party, once inclusive, has had, to say the least, a funny way of showing it. From every government department we regularly expect sallies against the very people who toil in the sector that the minister is supposed to lead. If there were at this moment a Ministry of Fruit Picking, you can be damn sure that the only way an ambitious Tory minister could advance his career would be by launching a blistering attack on the feckless indolence and inefficiency of fruit pickers.

It would be dishonest, however, to pretend any kind of nostalgia for the earlier, smugger form of conservatism. It is commonly said that leaders such as Harold Macmillan had either fought in the trenches or known men at first hand in their industrial constituencies and so gained a respect for working-class life, which the 21st-century leadership, with its upmarket aura of fine wine and evenings spent manspreading with sofa-sprawled box sets, conspicuously lacks. But this is to ignore the repellent layer of snobbery on which such sympathy relied. Even if, like me, you find the modern snobbery of a Notting Hill Cameron, who would rather be seen to be cool than to be caught out being compassionate, even more disgusting than the old-fashioned kind – because it is so much more cynical and calculated – nevertheless there was in the blimpish tone of the old conservatism an air of right-to-rule that saw the country as its plaything and government as its entitlement. Winston Churchill’s outrage at being booted out at the end of the second world war and the ruling class’s linking of the words “inexplicable” and “ingratitude” in the face of the hugely beneficial result speaks of an entire class culture that had at its heart a group resolution neither to understand nor to explain.

As the years have passed, the contradictions within conservatism have seemed to reach some kind of breaking point at which it is very hard to see how its central tenets can continue to make sense. Admittedly, since the severe recession brought about by the banks, Conservative administrations have found favour with the electorate while Labour has languished. At the election a year ago, Conservatives did somehow scrape together votes from almost 24% of the electorate. But such an outcome has done nothing to shake my basic conviction. In its essential thinking, the Tory project is bust.

The origins of conservatism’s modern incoherence lie with Thatcher. Whatever your view of her influence, she was different from her predecessors in her degree of intellectuality. She was unusually interested in ideas. Groomed by Chicago economists, she believed that Britain, robbed of the easy commercial advantages of its imperial reach, could thenceforth only prosper if it became competitive with China, with Japan, with America and with Germany. For this reason, in 1979, a crackpot theory called monetarism was briefly put into practice and allowed to wreak the havoc that destroyed one fifth of British industry. As soon as this futile theory had been painfully discredited, Conservative minds switched to obsessing on what they really wanted: the promotion and propagation of the so-called free market. If a previous form of patrician conservatism had been about respectability and social structure, this new form was about replacing all notions of public enterprise with a striving doctrine of individualism.

It is painful to point out how completely this grafting of foreign ideas onto the British economy has failed. The financial crash of 2008 dispelled once and for all the ingenious theory of the free market. The only thing, ideologues had argued, that could distort a market was the imposition of unnecessary rules and regulations by a third party, which had no vested interest in the outcome of the transaction and that was therefore a meddling force that robbed markets of their magnificent, near-mystical wisdom. These meddling forces were called governments. The flaw in the theory became apparent as soon as it was proved, once and for all, that irresponsible behaviour in a market did not simply affect the parties involved but could also, thanks to the knock-on effects of modern derivatives, bring whole national economies to their knees. The crappy practices of the banks did not punish only the guilty. Over and over, they punished the innocent far more cruelly. The myth of the free market had turned out to be exactly that: a myth, a Trotsykite fantasy, not real life.

Even disciples of Milton Friedman in Chicago were willing to admit the scale of the rout. They openly used the words “Back to the drawing board”. But in an astonishing act of corporate blackmail, the banks themselves then insisted that they be subsidised by the state. The very same taxpayers whom they had just defrauded had to dig in their pockets to pay for the bankers’ offences. Although state aid could no longer be tolerated as a good thing for regular citizens, who, it was said, were prone to becoming depraved, spoilt and junk-food-dependent when offered free money, subsidy could still be offered, when needed, on a dazzling scale, to benefit those who were already among our country’s most privileged and who were, by coincidence, the sole progenitors of its economic collapse. What a stroke of luck! Socialism, too good for the poor, turned out to be just the ticket for the rich.

It was the Labour government of Gordon Brown that consented to this first act of blackmail. It had little choice. There were dark threats from the banks of taking the whole country down with them. But it was the City-friendly Conservatives, learning nothing from history, who caved in without protest to a second, more outrageous wave of blackmail. The banks that had led us into the recession then argued that they were the only people who could lead us out. And the only way they could restore prosperity, they insisted, was by returning unpunished to exactly the same practices that had precipitated the crisis in the first place.

It has become impossible for any Conservative to argue for a free market when they do everything in their power to forbid free movement of labour. One is impossible without the other. A market, by definition, cannot be free if it operates behind artificial walls, or if it deliberately excludes traders who can offer their goods and services at a more competitive price. At the moment many such traders are volunteering to arrive and lend our market exactly the vigour that Conservatives always say it needs. But all too many of them, whether from Aleppo or from Tripoli, are dying with their children in open boats in the Mediterranean because the home secretary, Theresa May, is telling them that when she talks of the “free market”, she doesn’t actually mean it. She means “protected market”. She means “our market”. She means “market for people like us”. How can anyone with a trace of consistency or personal honour stand up and declare that international competitiveness is the sole criterion of national success, while at the same time excluding from that competition anyone who can compete better than you? Economic migrants, showing exactly the qualities of risk-taking, courage, independence, and family responsibility that Conservatives affect to admire are invited by May to plunge to their deaths in the sea rather than to trade.

The outcome of the Conservatives’ 30-year love affair with the idea that Britain is at heart no different from China, †he US or Germany, has inevitably been a sense of threat to the idea of national identity. Once Thatcher surrendered a native British conservatism to an American one, she knew full well that the side-effect would be to destroy ties and communities that held society together. By her own policies, she was reduced to petulant gestures. At Downing Street receptions she replaced the despised Perrier with good British Malvern water, but nobody was fooled. If international capital did indeed rule the world, then nothing made Britain special. On the contrary, it was on its way to being little more than a brand, defined, presumably, by the union jack, Cilla Black, Shakespeare, Jimmy Savile, Merrydown cider, and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. “We are a grandmother,” offered to cameras in the street on the birth of her first grandchild, represented a grammatical formulation halfway between patriotism and lunacy, intended to suggest the unique syntactical glamour of the English language. With the flick of a single pronoun, anyone could make themselves royalty. But on Thatcher’s watch, Britishness was now just bunting, a Falklands mug, a pretence.

Since then, successive Conservative governments have agonised long-windedly about the problem of how to make citizens loyal to a nation at the very moment when they are declaring the primacy of the economic system over the local culture. Their words die as soon as spoken, because everyone can see that if a government is unwilling to lift a finger to save those few organisations – like, for example, the steel industry – that do indeed forge communities, then all their rhetoric is so much guff. The home secretary, hitting syllables with a hammer as to a backward class of four year-olds, gloweringly asks everyone to share what she calls “British values”. Yet her own values, which she shares with the gilded David Cameron and George Osborne, include support for drone strikes and targeted assassination, the right to intercept private communications, the intention to curtail freedom of speech, the imposition of impossible limits on industrial action, a fierce contempt for any of the sick or unfortunate who have relied on the support of the state in order to stay alive, and a policy of selling lethal weapons to totalitarian allies who use them to bomb schools. The home secretary contemplates with equanimity the figure of the 2,380 disabled people who died in the little more than two years following Ian Duncan Smith’s legislation that recategorised them as “fit to work”. I don’t. By these standards, am I even British? Do I “share values” with Theresa May? Do I hell.

There will certainly be those who think me wistful in imagining that just because a headbangers’ conservatism no longer makes any intellectual sense that it is therefore finished. You will point, correctly, to the resilience of the Tory party and its ability to adapt at all times to changing circumstance. In the autumn of 2015, Jeremy Hunt, the health secretary, ready to warn us of what he insisted with relish were the harsh realities of global capitalism – Oh God, how Tories love saying “harsh realities” – insisted that Britain could only compete with China if it lowered state benefits and slashed tax credits for working people. It was, he said, essential for our whole future as a nation. But when George Osborne, the chancellor of the exchequer, then reversed his announced plan to slash those tax credits because such slashing would have represented a threat to his own advancement to Downing Street, that same Jeremy Hunt fell, on the instant, conspicuously silent.

It is, you may think, exactly such calculating practicality that is keeping the Tory ship floating long after its engine has died. You will add that the problems of how individual cultures are to endure the assaults of global corporations are, after all, not confined to Britain. Even if the government were of a radically different colour, you may say, it too would be facing the almost impossible challenge of asking how any country is to maintain meaningful democracy in the face of a predatory capitalism run by a kleptocratic class, which feels entitled to skim money at will. Would any faction honestly do better than the Tories at dealing with businesses run for no other purpose than the personal enrichment of their executives?

David Cameron arrived in office aware that a conservatism that was purely economic could not possibly meet the needs of the country, and therefore chose to advance an unlikely system of volunteerism, which he called the “big society”. It was, self-evidently, a palliative, nothing more, the lazy shrug of a faltering conscience, and one that predictably lasted no longer than the life cycle of a mosquito. Alert to a problem, Cameron lacked the fortitude to pursue its solution. Instead, Conservative ministers have fallen back on the more familiar, far more routine strategy of sour rhetoric, petulantly blaming the people for their failure to live up to the promise of their leaders’ policies. Do you have to be my age to remember a time when politicians aimed to lead, rather than to lecture? Is anyone old enough to recall a government whose ostensible mission was to serve us, not to improve us? When did magnanimity cease to be one of those famous British virtues we are ordered to share?

Commentators excoriate the politics of envy, but the politics of spite gets a free pass. Jeremy Hunt hates doctors. Theresa May despises the police. John Whittingdale resents public broadcasters. Chris Grayling loathed prison officers and Michael Gove famously had it in for teachers. Nowadays that’s what is called politics and that’s all politicians, Conservative-style, do. They voice grievances against a stubborn electorate that is never as far-seeing or radical as they are. Like Blair before him, Cameron has reduced the act of government to a sort of murmuring grudge, a resentment, in which politicians continually tell the surly people that we lack the necessary virtues for survival in the modern world. They know perfectly well that we hate them, and so their only response is to hate us back. Politics has been reduced to a sort of institutionalised nagging, in which a rack of pampered professionals, cut from the eye of the ruling class, tells everyone else that they don’t “get it”, and that they must “measure up” and “change their ways”. Having discharged their analysis, the preachers then invariably scoot off through wide-open doors to 40th-floor boardrooms to make themselves frictionless fortunes as greasers and lobbyists – or, as they prefer to say, “consultants”.

Of all the privatisations of the last 30 years, none has been more catastrophic than the privatisation of virtue. A doctor recently remarked that she was happy to put up with long hours and underpayment because she knew she was working in the service of an ideal. But, she said, if the NHS were so reorganised that she were then asked to suffer the same degree of overwork to provide profits for some rip-off private health company, she would walk away and refuse. In describing her motivation in this simple way, she put her finger on everything that has gone wrong in Britain under the tyranny of abstract ideas. Why do we work? Who are we working for? As Groucho Marx once asked: “If work’s so great, why don’t the rich do it?” People are ready, happy and willing to do things for our common benefit that they are reluctant to do if it is all in the interests of companies such as British Telecom, Virgin Railways, EDF Energy, Talk Talk, HSBC, Kraft Foods and Barclays Bank, outfits that still have little or no interest in balancing out their prosperity in a fair manner between their employees and their shareholders.

The reason we have been governed so badly is because government has been in the hands of those who least believe in it. Politicians have become little more than go-betweens, their principal function to hand over taxpayers’ assets, always in car boot sales and always at way less than market value. No longer having faith in their own competence, politicians have blithely surrendered the state’s most basic duties. Even the care and detention of prisoners, and thereby the protection of citizens from danger, has been given to contractors, as though the state no longer trusted itself to open a gate, build a wall, or serve a three-course meal. With foreign policy delegated to Washington, and consciences delegated by private contract to callous logistics companies, no wonder the profession of politics in Britain is having a nervous breakdown of its own making.

In the years after the second world war, under successive administrations of either party, we profited from purposeful initiatives, building the welfare state, the housing stock and the NHS. We voted for leaders who shared a common-sense belief that government was necessary to do good. They entered politics partly because they believed in its essential usefulness. How strange it is, then, this new breed of self-hating politicians who want to make a healthy living in politics, while at the same time insisting that the only function of politics is to get out of the way of private enterprise. Ever since Ronald Reagan announced that he would campaign on a platform of smaller government, it has been an article of faith on the right to insist that the state must play an ever smaller part in the country’s affairs. But the paradox of a Thatcher or a Reagan is that they fulminate all the time against the state while living lavishly off it. Our current administration advises everyone else to strip back and face the new demands of austerity. Meanwhile, it employs 68 unelected special advisers to fix Tory policy at taxpayers’ expense, while busily ordering a private jet for the prime minister’s travel.

How did we get here? And how do we move on? Prince Charles, questioning a monk in Kyoto about the road to enlightenment, was asked in reply if he could ever forget that he was a prince. “Of course not,” Charles replied, “One’s always aware of it. One’s always aware one’s a prince.” In that case, said the monk, he would never know the road to enlightenment. A similar need to forget our pretensions must newly govern our politics. We do not live in a free market. No such thing as a free market exists. Nor can it. The world is far too complex, far too interconnected. All markets are rigged. The only question that need concern us is: in whose interest? In the light of this question, obsessive Tory spasms about Europe are revealed as a doomed attempt to re-rig the market even further in their own favour, so that the same exclusion orders that prevent Syrians and Libyans from threatening our carefully protected wealth should in future keep out over-eager Hungarians, Poles, Bulgarians and Romanians. Far from wishing to free the country to compete in the world, anti-European Union sentiment in Britain is, in Tory hearts, about protecting Britain yet more effectively.

The first task British politics has to address is correcting the terrible harm we have done ourselves by assuming that nothing can be achieved through collective enterprise. It is as much a failure of national imagination as it is of national will. When I woke up on the morning after Knuckle opened in London, on 5 March 1974, then the stinging impact of the play’s rejection by audiences and critics alike forced me finally to admit to myself that I was not just a theatre director who happened to write, but that I was, indeed, going to spend the rest of my life as a professional playwright.

In the 1980s and 1990s, my attention turned to the people on the front line who helped bind the wounds of communities shattered by Thatcherism. In plays such as Skylight and Racing Demon and Murmuring Judges, I was able to portray teachers and vicars and police and prison officers who, newly politicised, saw their jobs as trying to tackle the everyday problems caused by a reckless ideology. I loved writing about such hands-on practical people because I admired them. They became my heroes and heroines. But even as I tried to discredit the publicity that saw Thatcherism as liberating, I was still reluctant to propose a counter-myth, which pictured the government of 1945 as a permanent model of perfection. Requested over and again to write films and plays about the National Health Service, I always refused because I was reluctant to make too facile a comparison. How could I write on the subject without seeming to imply that once we had ideals, and that now we didn’t?

Our current politics are governed by two competing nostalgias, both of them pieties. Conservatives seek to locate all good in Thatcherism and the 1980s, and in the unworkable nonsense of the free market, while Labour seeks to locate it in 1945 and an industrial society, which, for better or worse, no longer exists. And yet issues of justice remain, and always will. Conservativism, as presently formulated, is unworkable in the UK because it continues to demand that citizens from so many different backgrounds and cultures identify with a society organised in ways that are outrageously unfair. The bullying rhetorical project of seeking to blame diversity for the crimes of inequity is doomed to fail. You cannot pamper the rich, punish the poor, cut benefits and then say: “Now feel British!”

There is a bleak fatalism at the heart of conservatism, which has been codified into the lie that the market can only do what the market does, and that we must therefore watch powerless. We have seen the untruth of this in the successful interventions governments have recently made on behalf of the rich. Now we long for many more such interventions on behalf of everyone else. Often, in the past 40 years, I refused to contemplate writing plays that might imply that public idealism was dead. From observing the daily lives of those in public service, I know this not to be true. But we lack two things: new ways of channelling such idealism into practical instruments of policy, and a political class that is not disabled by its philosophy from the job of realising them. If we talk seriously about British values, then the noblest and most common of them all used to be the conviction that, with will and enlightenment, historical change could be managed. We did not have to be its victims. Its cruelties could be mitigated. Why, then, is the current attitude that we must surrender to it? I had asked this question at the Oxford Playhouse in 1974 as I walked back down a darkened Beaumont Street to a hotel of draped velvet curtains, power outages and guttering candles. I ask it again today.