“Blessed is the nation that doesn’t need heroes" Goethe. “Hero-worship is strongest where there is least regard for human freedom.” Herbert Spencer

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label meditation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label meditation. Show all posts

Friday 30 July 2021

Friday 14 June 2019

The mindfulness conspiracy - Is Meditation the enemy of Activism?

It is sold as a force that can help us cope with the ravages of capitalism, but with its inward focus, mindful meditation may be the enemy of activism. By Ronald Purser in The Guardian

Mindfulness has gone mainstream, with celebrity endorsement from Oprah Winfrey and Goldie Hawn. Meditation coaches, monks and neuroscientists went to Davos to impart the finer points to CEOs attending the World Economic Forum. The founders of the mindfulness movement have grown evangelical. Prophesying that its hybrid of science and meditative discipline “has the potential to ignite a universal or global renaissance”, the inventor of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Jon Kabat-Zinn, has bigger ambitions than conquering stress. Mindfulness, he proclaims, “may actually be the only promise the species and the planet have for making it through the next couple of hundred years”.

So, what exactly is this magic panacea? In 2014, Time magazine put a youthful blonde woman on its cover, blissing out above the words: “The Mindful Revolution.” The accompanying feature described a signature scene from the standardised course teaching MBSR: eating a raisin very slowly. “The ability to focus for a few minutes on a single raisin isn’t silly if the skills it requires are the keys to surviving and succeeding in the 21st century,” the author explained.

But anything that offers success in our unjust society without trying to change it is not revolutionary – it just helps people cope. In fact, it could also be making things worse. Instead of encouraging radical action, mindfulness says the causes of suffering are disproportionately inside us, not in the political and economic frameworks that shape how we live. And yet mindfulness zealots believe that paying closer attention to the present moment without passing judgment has the revolutionary power to transform the whole world. It’s magical thinking on steroids.

There are certainly worthy dimensions to mindfulness practice. Tuning out mental rumination does help reduce stress, as well as chronic anxiety and many other maladies. Becoming more aware of automatic reactions can make people calmer and potentially kinder. Most of the promoters of mindfulness are nice, and having personally met many of them, including the leaders of the movement, I have no doubt that their hearts are in the right place. But that isn’t the issue here. The problem is the product they’re selling, and how it’s been packaged. Mindfulness is nothing more than basic concentration training. Although derived from Buddhism, it’s been stripped of the teachings on ethics that accompanied it, as well as the liberating aim of dissolving attachment to a false sense of self while enacting compassion for all other beings.

What remains is a tool of self-discipline, disguised as self-help. Instead of setting practitioners free, it helps them adjust to the very conditions that caused their problems. A truly revolutionary movement would seek to overturn this dysfunctional system, but mindfulness only serves to reinforce its destructive logic. The neoliberal order has imposed itself by stealth in the past few decades, widening inequality in pursuit of corporate wealth. People are expected to adapt to what this model demands of them. Stress has been pathologised and privatised, and the burden of managing it outsourced to individuals. Hence the pedlars of mindfulness step in to save the day.

But none of this means that mindfulness ought to be banned, or that anyone who finds it useful is deluded. Reducing suffering is a noble aim and it should be encouraged. But to do this effectively, teachers of mindfulness need to acknowledge that personal stress also has societal causes. By failing to address collective suffering, and systemic change that might remove it, they rob mindfulness of its real revolutionary potential, reducing it to something banal that keeps people focused on themselves.

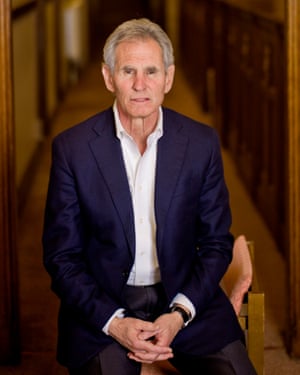

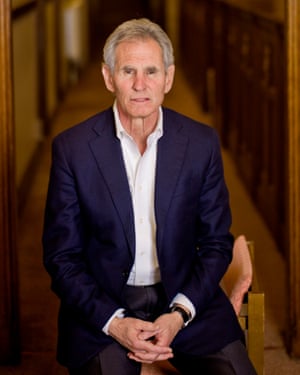

Jon Kabat-Zinn, who is often called the father of modern mindfulness. Photograph: Sarah Lee

The fundamental message of the mindfulness movement is that the underlying cause of dissatisfaction and distress is in our heads. By failing to pay attention to what actually happens in each moment, we get lost in regrets about the past and fears for the future, which make us unhappy. Kabat-Zinn, who is often labelled the father of modern mindfulness, calls this a “thinking disease”. Learning to focus turns down the volume on circular thought, so Kabat-Zinn’s diagnosis is that our “entire society is suffering from attention deficit disorder – big time”. Other sources of cultural malaise are not discussed. The only mention of the word “capitalist” in Kabat-Zinn’s book Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness occurs in an anecdote about a stressed investor who says: “We all suffer a kind of ADD.”

Mindfulness advocates, perhaps unwittingly, are providing support for the status quo. Rather than discussing how attention is monetised and manipulated by corporations such as Google, Facebook, Twitter and Apple, they locate the crisis in our minds. It is not the nature of the capitalist system that is inherently problematic; rather, it is the failure of individuals to be mindful and resilient in a precarious and uncertain economy. Then they sell us solutions that make us contented, mindful capitalists.

By practising mindfulness, individual freedom is supposedly found within “pure awareness”, undistracted by external corrupting influences. All we need to do is close our eyes and watch our breath. And that’s the crux of the supposed revolution: the world is slowly changed, one mindful individual at a time. This political philosophy is oddly reminiscent of George W Bush’s “compassionate conservatism”. With the retreat to the private sphere, mindfulness becomes a religion of the self. The idea of a public sphere is being eroded, and any trickledown effect of compassion is by chance. As a result, notes the political theorist Wendy Brown, “the body politic ceases to be a body, but is, rather, a group of individual entrepreneurs and consumers”.

Mindfulness, like positive psychology and the broader happiness industry, has depoliticised stress. If we are unhappy about being unemployed, losing our health insurance, and seeing our children incur massive debt through college loans, it is our responsibility to learn to be more mindful. Kabat-Zinn assures us that “happiness is an inside job” that simply requires us to attend to the present moment mindfully and purposely without judgment. Another vocal promoter of meditative practice, the neuroscientist Richard Davidson, contends that “wellbeing is a skill” that can be trained, like working out one’s biceps at the gym. The so-called mindfulness revolution meekly accepts the dictates of the marketplace. Guided by a therapeutic ethos aimed at enhancing the mental and emotional resilience of individuals, it endorses neoliberal assumptions that everyone is free to choose their responses, manage negative emotions, and “flourish” through various modes of self-care. Framing what they offer in this way, most teachers of mindfulness rule out a curriculum that critically engages with causes of suffering in the structures of power and economic systems of capitalist society.

The term “McMindfulness” was coined by Miles Neale, a Buddhist teacher and psychotherapist, who described “a feeding frenzy of spiritual practices that provide immediate nutrition but no long-term sustenance”. The contemporary mindfulness fad is the entrepreneurial equal of McDonald’s. The founder of McDonald’s, Ray Kroc, created the fast food industry. Very early on, when he was selling milkshakes, Kroc spotted the franchising potential of a restaurant chain in San Bernadino, California. He made a deal to serve as the franchising agent for the McDonald brothers. Soon afterwards, he bought them out, and grew the chain into a global empire. Kabat-Zinn, a dedicated meditator, had a vision in the midst of a retreat: he could adapt Buddhist teachings and practices to help hospital patients deal with physical pain, stress and anxiety. His masterstroke was the branding of mindfulness as a secular spirituality.

Kroc saw his chance to provide busy Americans with instant access to food that would be delivered consistently through automation, standardisation and discipline. Kabat-Zinn perceived the opportunity to give stressed-out Americans easy access to MBSR through an eight-week mindfulness course for stress reduction that would be taught consistently using a standardised curriculum. MBSR teachers would gain certification by attending programmes at Kabat-Zinn’s Center for Mindfulness in Worcester, Massachusetts. He continued to expand the reach of MBSR by identifying new markets such as corporations, schools, government and the military, and endorsing other forms of “mindfulness-based interventions” (MBIs).

Both men took measures to ensure that their products would not vary in quality or content across franchises. Burgers and fries at McDonald’s are the same whether one is eating them in Dubai or in Dubuque. Similarly, there is little variation in the content, structuring and curriculum of MBSR courses around the world.

From inboxing to thought showers: how business bullshit took over

All the promises of mindfulness resonate with what the University of Chicago cultural theorist Lauren Berlant calls “cruel optimism”, a defining neoliberal characteristic. It is cruel in that one makes affective investments in what amount to fantasies. We are told that if we practice mindfulness, and get our individual lives in order, we can be happy and secure. It is therefore implied that stable employment, home ownership, social mobility, career success and equality will naturally follow. We are also promised that we can gain self-mastery, controlling our minds and emotions so we can thrive and flourish amid the vagaries of capitalism.As Joshua Eisen, the author of Mindful Calculations, puts it: “Like kale, acai berries, gym memberships, vitamin water, and other new year’s resolutions, mindfulness indexes a profound desire to change, but one premised on a fundamental reassertion of neoliberal fantasies of self-control and unfettered agency.” We just have to sit in silence, watching our breath, and wait. It is doubly cruel because these normative fantasies of the “good life” are already crumbling under neoliberalism, and we make it worse if we focus individually on our feelings. Neglecting shared vulnerabilities and interdependence, we disimagine the collective ways we might protect ourselves. And despite the emptiness of nurturing fantasies, we continue to cling to them.

Mindfulness isn’t cruel in and of itself. It’s only cruel when fetishised and attached to inflated promises. It is then, as Berlant points out, that “the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially”. The cruelty lies in supporting the status quo while using the language of transformation. This is how neoliberal mindfulness promotes an individualistic vision of human flourishing, enticing us to accept things as they are, mindfully enduring the ravages of capitalism.

Mindfulness has gone mainstream, with celebrity endorsement from Oprah Winfrey and Goldie Hawn. Meditation coaches, monks and neuroscientists went to Davos to impart the finer points to CEOs attending the World Economic Forum. The founders of the mindfulness movement have grown evangelical. Prophesying that its hybrid of science and meditative discipline “has the potential to ignite a universal or global renaissance”, the inventor of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Jon Kabat-Zinn, has bigger ambitions than conquering stress. Mindfulness, he proclaims, “may actually be the only promise the species and the planet have for making it through the next couple of hundred years”.

So, what exactly is this magic panacea? In 2014, Time magazine put a youthful blonde woman on its cover, blissing out above the words: “The Mindful Revolution.” The accompanying feature described a signature scene from the standardised course teaching MBSR: eating a raisin very slowly. “The ability to focus for a few minutes on a single raisin isn’t silly if the skills it requires are the keys to surviving and succeeding in the 21st century,” the author explained.

But anything that offers success in our unjust society without trying to change it is not revolutionary – it just helps people cope. In fact, it could also be making things worse. Instead of encouraging radical action, mindfulness says the causes of suffering are disproportionately inside us, not in the political and economic frameworks that shape how we live. And yet mindfulness zealots believe that paying closer attention to the present moment without passing judgment has the revolutionary power to transform the whole world. It’s magical thinking on steroids.

There are certainly worthy dimensions to mindfulness practice. Tuning out mental rumination does help reduce stress, as well as chronic anxiety and many other maladies. Becoming more aware of automatic reactions can make people calmer and potentially kinder. Most of the promoters of mindfulness are nice, and having personally met many of them, including the leaders of the movement, I have no doubt that their hearts are in the right place. But that isn’t the issue here. The problem is the product they’re selling, and how it’s been packaged. Mindfulness is nothing more than basic concentration training. Although derived from Buddhism, it’s been stripped of the teachings on ethics that accompanied it, as well as the liberating aim of dissolving attachment to a false sense of self while enacting compassion for all other beings.

What remains is a tool of self-discipline, disguised as self-help. Instead of setting practitioners free, it helps them adjust to the very conditions that caused their problems. A truly revolutionary movement would seek to overturn this dysfunctional system, but mindfulness only serves to reinforce its destructive logic. The neoliberal order has imposed itself by stealth in the past few decades, widening inequality in pursuit of corporate wealth. People are expected to adapt to what this model demands of them. Stress has been pathologised and privatised, and the burden of managing it outsourced to individuals. Hence the pedlars of mindfulness step in to save the day.

But none of this means that mindfulness ought to be banned, or that anyone who finds it useful is deluded. Reducing suffering is a noble aim and it should be encouraged. But to do this effectively, teachers of mindfulness need to acknowledge that personal stress also has societal causes. By failing to address collective suffering, and systemic change that might remove it, they rob mindfulness of its real revolutionary potential, reducing it to something banal that keeps people focused on themselves.

Jon Kabat-Zinn, who is often called the father of modern mindfulness. Photograph: Sarah Lee

The fundamental message of the mindfulness movement is that the underlying cause of dissatisfaction and distress is in our heads. By failing to pay attention to what actually happens in each moment, we get lost in regrets about the past and fears for the future, which make us unhappy. Kabat-Zinn, who is often labelled the father of modern mindfulness, calls this a “thinking disease”. Learning to focus turns down the volume on circular thought, so Kabat-Zinn’s diagnosis is that our “entire society is suffering from attention deficit disorder – big time”. Other sources of cultural malaise are not discussed. The only mention of the word “capitalist” in Kabat-Zinn’s book Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness occurs in an anecdote about a stressed investor who says: “We all suffer a kind of ADD.”

Mindfulness advocates, perhaps unwittingly, are providing support for the status quo. Rather than discussing how attention is monetised and manipulated by corporations such as Google, Facebook, Twitter and Apple, they locate the crisis in our minds. It is not the nature of the capitalist system that is inherently problematic; rather, it is the failure of individuals to be mindful and resilient in a precarious and uncertain economy. Then they sell us solutions that make us contented, mindful capitalists.

By practising mindfulness, individual freedom is supposedly found within “pure awareness”, undistracted by external corrupting influences. All we need to do is close our eyes and watch our breath. And that’s the crux of the supposed revolution: the world is slowly changed, one mindful individual at a time. This political philosophy is oddly reminiscent of George W Bush’s “compassionate conservatism”. With the retreat to the private sphere, mindfulness becomes a religion of the self. The idea of a public sphere is being eroded, and any trickledown effect of compassion is by chance. As a result, notes the political theorist Wendy Brown, “the body politic ceases to be a body, but is, rather, a group of individual entrepreneurs and consumers”.

Mindfulness, like positive psychology and the broader happiness industry, has depoliticised stress. If we are unhappy about being unemployed, losing our health insurance, and seeing our children incur massive debt through college loans, it is our responsibility to learn to be more mindful. Kabat-Zinn assures us that “happiness is an inside job” that simply requires us to attend to the present moment mindfully and purposely without judgment. Another vocal promoter of meditative practice, the neuroscientist Richard Davidson, contends that “wellbeing is a skill” that can be trained, like working out one’s biceps at the gym. The so-called mindfulness revolution meekly accepts the dictates of the marketplace. Guided by a therapeutic ethos aimed at enhancing the mental and emotional resilience of individuals, it endorses neoliberal assumptions that everyone is free to choose their responses, manage negative emotions, and “flourish” through various modes of self-care. Framing what they offer in this way, most teachers of mindfulness rule out a curriculum that critically engages with causes of suffering in the structures of power and economic systems of capitalist society.

The term “McMindfulness” was coined by Miles Neale, a Buddhist teacher and psychotherapist, who described “a feeding frenzy of spiritual practices that provide immediate nutrition but no long-term sustenance”. The contemporary mindfulness fad is the entrepreneurial equal of McDonald’s. The founder of McDonald’s, Ray Kroc, created the fast food industry. Very early on, when he was selling milkshakes, Kroc spotted the franchising potential of a restaurant chain in San Bernadino, California. He made a deal to serve as the franchising agent for the McDonald brothers. Soon afterwards, he bought them out, and grew the chain into a global empire. Kabat-Zinn, a dedicated meditator, had a vision in the midst of a retreat: he could adapt Buddhist teachings and practices to help hospital patients deal with physical pain, stress and anxiety. His masterstroke was the branding of mindfulness as a secular spirituality.

Kroc saw his chance to provide busy Americans with instant access to food that would be delivered consistently through automation, standardisation and discipline. Kabat-Zinn perceived the opportunity to give stressed-out Americans easy access to MBSR through an eight-week mindfulness course for stress reduction that would be taught consistently using a standardised curriculum. MBSR teachers would gain certification by attending programmes at Kabat-Zinn’s Center for Mindfulness in Worcester, Massachusetts. He continued to expand the reach of MBSR by identifying new markets such as corporations, schools, government and the military, and endorsing other forms of “mindfulness-based interventions” (MBIs).

Both men took measures to ensure that their products would not vary in quality or content across franchises. Burgers and fries at McDonald’s are the same whether one is eating them in Dubai or in Dubuque. Similarly, there is little variation in the content, structuring and curriculum of MBSR courses around the world.

Illustration: Patryk Sroczyński

Mindfulness has been oversold and commodified, reduced to a technique for just about any instrumental purpose. It can give inner-city kids a calming time-out, or hedge-fund traders a mental edge, or reduce the stress of military drone pilots. Void of a moral compass or ethical commitments, unmoored from a vision of the social good, the commodification of mindfulness keeps it anchored in the ethos of the market.

This has come about partly because proponents of mindfulness believe that the practice is apolitical, and so the avoidance of moral inquiry and the reluctance to consider a vision of the social good are intertwined. It is simply assumed that ethical behaviour will arise “naturally” from practice and the teacher’s “embodiment” of soft-spoken niceness, or through the happenstance of self-discovery. However, the claim that major ethical changes will follow from “paying attention to the present moment, non-judgmentally” is patently flawed. The emphasis on “non-judgmental awareness” can just as easily disable one’s moral intelligence.

In Selling Spirituality: The Silent Takeover of Religion, Jeremy Carrette and Richard King argue that traditions of Asian wisdom have been subject to colonisation and commodification since the 18th century, producing a highly individualistic spirituality, perfectly accommodated to dominant cultural values and requiring no substantive change in lifestyle. Such an individualistic spirituality is clearly linked with the neoliberal agenda of privatisation, especially when masked by the ambiguous language used in mindfulness. Market forces are already exploiting the momentum of the mindfulness movement, reorienting its goals to a highly circumscribed individual realm.

Mindfulness is easily co-opted and reduced to merely “pacifying feelings of anxiety and disquiet at the individual level, rather than seeking to challenge the social, political and economic inequalities that cause such distress”, write Carrette and King. But a commitment to this kind of privatised and psychologised mindfulness is political – therapeutically optimising individuals to make them “mentally fit”, attentive and resilient, so they may keep functioning within the system. Such capitulation seems like the farthest thing from a revolution – more like a quietist surrender.

Mindfulness is positioned as a force that can help us cope with the noxious influences of capitalism. But because what it offers is so easily assimilated by the market, its potential for social and political transformation is neutered. Leaders in the mindfulness movement believe that capitalism and spirituality can be reconciled; they want to relieve the stress of individuals without having to look deeper and more broadly at its causes.

Mindfulness is being sold to executives as a way to de-stress, focus and bounce back from working 80-hour weeks

A truly revolutionary mindfulness would challenge the western sense of entitlement to happiness irrespective of ethical conduct. However, mindfulness programmes do not ask executives to examine how their managerial decisions and corporate policies have institutionalised greed, ill will and delusion. Instead, the practice is being sold to executives as a way to de-stress, improve productivity and focus, and bounce back from working 80-hour weeks. They may well be “meditating”, but it works like taking an aspirin for a headache. Once the pain goes away, it is business as usual. Even if individuals become nicer people, the corporate agenda of maximising profits does not change.

If mindfulness just helps people cope with the toxic conditions that make them stressed in the first place, then perhaps we could aim a bit higher. Should we celebrate the fact that this perversion is helping people to “auto-exploit” themselves? This is the core of the problem. The internalisation of focus for mindfulness practice also leads to other things being internalised, from corporate requirements to structures of dominance in society. Perhaps worst of all, this submissive position is framed as freedom. Indeed, mindfulness thrives on doublespeak about freedom, celebrating self-centered “freedoms” while paying no attention to civic responsibility, or the cultivation of a collective mindfulness that finds genuine freedom within a co-operative and just society.

Of course, reductions in stress and increases in personal happiness and wellbeing are much easier to sell than serious questions about injustice, inequity and environmental devastation. The latter involve a challenge to the social order, while the former play directly to mindfulness’s priorities – sharpening people’s focus, improving their performance at work and in exams, and even promising better sex lives. Not only has mindfulness been repackaged as a novel technique of psychotherapy, but its utility is commercially marketed as self-help. This branding reinforces the notion that spiritual practices are indeed an individual’s private concern. And once privatised, these practices are easily co-opted for social, economic and political control.

Rather than being used as a means to awaken individuals and organisations to the unwholesome roots of greed, ill will and delusion, mindfulness is more often refashioned into a banal, therapeutic, self-help technique that can actually reinforce those roots.

Mindfulness is said to be a $4bn industry. More than 60,000 books for sale on Amazon have a variant of “mindfulness” in their title, touting the benefits of Mindful Parenting, Mindful Eating, Mindful Teaching, Mindful Therapy, Mindful Leadership, Mindful Finance, a Mindful Nation, and Mindful Dog Owners, to name just a few. There is also The Mindfulness Colouring Book, part of a bestselling subgenre in itself. Besides books, there are workshops, online courses, glossy magazines, documentary films, smartphone apps, bells, cushions, bracelets, beauty products and other paraphernalia, as well as a lucrative and burgeoning conference circuit. Mindfulness programmes have made their way into schools, Wall Street and Silicon Valley corporations, law firms, and government agencies, including the US military.

The presentation of mindfulness as a market-friendly palliative explains its warm reception in popular culture. It slots so neatly into the mindset of the workplace that its only real threat to the status quo is to offer people ways to become more skilful at the rat race. Modern society’s neoliberal consensus argues that those who enjoy power and wealth should be given free rein to accumulate more. It’s perhaps no surprise that those mindfulness merchants who accept market logic are a hit with the CEOs in Davos, where Kabat-Zinn has no qualms about preaching the gospel of competitive advantage from meditative practice.

Over the past few decades, neoliberalism has outgrown its conservative roots. It has hijacked public discourse to the extent that even self-professed progressives, such as Kabat-Zinn, think in neoliberal terms. Market values have invaded every corner of human life, defining how most of us are forced to interpret and live in the world.

Perhaps the most straightforward definition of neoliberalism comes from the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who calls it “a programme for destroying collective structures that may impede the pure market logic”. We are generally conditioned to think that a market-based society provides us with ample (if not equal) opportunities for increasing the value of our “human capital” and self-worth. And in order to fully actualise personal freedom and potential, we need to maximise our own welfare, freedom, and happiness by deftly managing internal resources.

Since competition is so central, neoliberal ideology holds that all decisions about how society is run should be left to the workings of the marketplace, the most efficient mechanism for allowing competitors to maximise their own good. Other social actors – including the state, voluntary associations, and the like – are just obstacles to the smooth operation of market logic.

Mindfulness has been oversold and commodified, reduced to a technique for just about any instrumental purpose. It can give inner-city kids a calming time-out, or hedge-fund traders a mental edge, or reduce the stress of military drone pilots. Void of a moral compass or ethical commitments, unmoored from a vision of the social good, the commodification of mindfulness keeps it anchored in the ethos of the market.

This has come about partly because proponents of mindfulness believe that the practice is apolitical, and so the avoidance of moral inquiry and the reluctance to consider a vision of the social good are intertwined. It is simply assumed that ethical behaviour will arise “naturally” from practice and the teacher’s “embodiment” of soft-spoken niceness, or through the happenstance of self-discovery. However, the claim that major ethical changes will follow from “paying attention to the present moment, non-judgmentally” is patently flawed. The emphasis on “non-judgmental awareness” can just as easily disable one’s moral intelligence.

In Selling Spirituality: The Silent Takeover of Religion, Jeremy Carrette and Richard King argue that traditions of Asian wisdom have been subject to colonisation and commodification since the 18th century, producing a highly individualistic spirituality, perfectly accommodated to dominant cultural values and requiring no substantive change in lifestyle. Such an individualistic spirituality is clearly linked with the neoliberal agenda of privatisation, especially when masked by the ambiguous language used in mindfulness. Market forces are already exploiting the momentum of the mindfulness movement, reorienting its goals to a highly circumscribed individual realm.

Mindfulness is easily co-opted and reduced to merely “pacifying feelings of anxiety and disquiet at the individual level, rather than seeking to challenge the social, political and economic inequalities that cause such distress”, write Carrette and King. But a commitment to this kind of privatised and psychologised mindfulness is political – therapeutically optimising individuals to make them “mentally fit”, attentive and resilient, so they may keep functioning within the system. Such capitulation seems like the farthest thing from a revolution – more like a quietist surrender.

Mindfulness is positioned as a force that can help us cope with the noxious influences of capitalism. But because what it offers is so easily assimilated by the market, its potential for social and political transformation is neutered. Leaders in the mindfulness movement believe that capitalism and spirituality can be reconciled; they want to relieve the stress of individuals without having to look deeper and more broadly at its causes.

Mindfulness is being sold to executives as a way to de-stress, focus and bounce back from working 80-hour weeks

A truly revolutionary mindfulness would challenge the western sense of entitlement to happiness irrespective of ethical conduct. However, mindfulness programmes do not ask executives to examine how their managerial decisions and corporate policies have institutionalised greed, ill will and delusion. Instead, the practice is being sold to executives as a way to de-stress, improve productivity and focus, and bounce back from working 80-hour weeks. They may well be “meditating”, but it works like taking an aspirin for a headache. Once the pain goes away, it is business as usual. Even if individuals become nicer people, the corporate agenda of maximising profits does not change.

If mindfulness just helps people cope with the toxic conditions that make them stressed in the first place, then perhaps we could aim a bit higher. Should we celebrate the fact that this perversion is helping people to “auto-exploit” themselves? This is the core of the problem. The internalisation of focus for mindfulness practice also leads to other things being internalised, from corporate requirements to structures of dominance in society. Perhaps worst of all, this submissive position is framed as freedom. Indeed, mindfulness thrives on doublespeak about freedom, celebrating self-centered “freedoms” while paying no attention to civic responsibility, or the cultivation of a collective mindfulness that finds genuine freedom within a co-operative and just society.

Of course, reductions in stress and increases in personal happiness and wellbeing are much easier to sell than serious questions about injustice, inequity and environmental devastation. The latter involve a challenge to the social order, while the former play directly to mindfulness’s priorities – sharpening people’s focus, improving their performance at work and in exams, and even promising better sex lives. Not only has mindfulness been repackaged as a novel technique of psychotherapy, but its utility is commercially marketed as self-help. This branding reinforces the notion that spiritual practices are indeed an individual’s private concern. And once privatised, these practices are easily co-opted for social, economic and political control.

Rather than being used as a means to awaken individuals and organisations to the unwholesome roots of greed, ill will and delusion, mindfulness is more often refashioned into a banal, therapeutic, self-help technique that can actually reinforce those roots.

Mindfulness is said to be a $4bn industry. More than 60,000 books for sale on Amazon have a variant of “mindfulness” in their title, touting the benefits of Mindful Parenting, Mindful Eating, Mindful Teaching, Mindful Therapy, Mindful Leadership, Mindful Finance, a Mindful Nation, and Mindful Dog Owners, to name just a few. There is also The Mindfulness Colouring Book, part of a bestselling subgenre in itself. Besides books, there are workshops, online courses, glossy magazines, documentary films, smartphone apps, bells, cushions, bracelets, beauty products and other paraphernalia, as well as a lucrative and burgeoning conference circuit. Mindfulness programmes have made their way into schools, Wall Street and Silicon Valley corporations, law firms, and government agencies, including the US military.

The presentation of mindfulness as a market-friendly palliative explains its warm reception in popular culture. It slots so neatly into the mindset of the workplace that its only real threat to the status quo is to offer people ways to become more skilful at the rat race. Modern society’s neoliberal consensus argues that those who enjoy power and wealth should be given free rein to accumulate more. It’s perhaps no surprise that those mindfulness merchants who accept market logic are a hit with the CEOs in Davos, where Kabat-Zinn has no qualms about preaching the gospel of competitive advantage from meditative practice.

Over the past few decades, neoliberalism has outgrown its conservative roots. It has hijacked public discourse to the extent that even self-professed progressives, such as Kabat-Zinn, think in neoliberal terms. Market values have invaded every corner of human life, defining how most of us are forced to interpret and live in the world.

Perhaps the most straightforward definition of neoliberalism comes from the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who calls it “a programme for destroying collective structures that may impede the pure market logic”. We are generally conditioned to think that a market-based society provides us with ample (if not equal) opportunities for increasing the value of our “human capital” and self-worth. And in order to fully actualise personal freedom and potential, we need to maximise our own welfare, freedom, and happiness by deftly managing internal resources.

Since competition is so central, neoliberal ideology holds that all decisions about how society is run should be left to the workings of the marketplace, the most efficient mechanism for allowing competitors to maximise their own good. Other social actors – including the state, voluntary associations, and the like – are just obstacles to the smooth operation of market logic.

Illustration: Patryk Sroczyński

For an actor in neoliberal society, mindfulness is a skill to be cultivated, or a resource to be put to use. When mastered, it helps you to navigate the capitalist ocean’s tricky currents, keeping your attention “present-centred and non-judgmental” to deal with the inevitable stress and anxiety from competition. Mindfulness helps you to maximise your personal wellbeing.

All of this may help you to sleep better at night. But the consequences for society are potentially dire. The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek has analysed this trend. As he sees it, mindfulness is “establishing itself as the hegemonic ideology of global capitalism”, by helping people “to fully participate in the capitalist dynamic while retaining the appearance of mental sanity”.

By deflecting attention from the social structures and material conditions in a capitalist culture, mindfulness is easily co-opted. Celebrity role models bless and endorse it, while Californian companies including Google, Facebook, Twitter, Apple and Zynga have embraced it as an adjunct to their brand. Google’s former in-house mindfulness tsar Chade-Meng Tan had the actual job title Jolly Good Fellow. “Search inside yourself,” he counselled colleagues and readers – for there, not in corporate culture – lies the source of your problems.

The rhetoric of “self-mastery”, “resilience” and “happiness” assumes wellbeing is simply a matter of developing a skill. Mindfulness cheerleaders are particularly fond of this trope, saying we can train our brains to be happy, like exercising muscles. Happiness, freedom and wellbeing become the products of individual effort. Such so-called “skills” can be developed without reliance on external factors, relationships or social conditions. Underneath its therapeutic discourse, mindfulness subtly reframes problems as the outcomes of choices. Personal troubles are never attributed to political or socioeconomic conditions, but are always psychological in nature and diagnosed as pathologies. Society therefore needs therapy, not radical change. This is perhaps why mindfulness initiatives have become so attractive to government policymakers. Societal problems rooted in inequality, racism, poverty, addiction and deteriorating mental health can be reframed in terms of individual psychology, requiring therapeutic help. Vulnerable subjects can even be told to provide this themselves.

Neoliberalism divides the world into winners and losers. It accomplishes this task through its ideological linchpin: the individualisation of all social phenomena. Since the autonomous (and free) individual is the primary focal point for society, social change is achieved not through political protest, organising and collective action, but via the free market and atomised actions of individuals. Any effort to change this through collective structures is generally troublesome to the neoliberal order. It is therefore discouraged.

An illustrative example is the practice of recycling. The real problem is the mass production of plastics by corporations, and their overuse in retail. However, consumers are led to believe that being personally wasteful is the underlying issue, which can be fixed if they change their habits. As a recent essay in Scientific American scoffs: “Recycling plastic is to saving the Earth what hammering a nail is to halting a falling skyscraper.” Yet the neoliberal doctrine of individual responsibility has performed its sleight-of-hand, distracting us from the real culprit. This is far from new. In the 1950s, the “Keep America Beautiful” campaign urged individuals to pick up their trash. The project was bankrolled by corporations such as Coca-Cola, Anheuser-Busch and Phillip Morris, in partnership with the public service announcement Ad Council, which coined the term “litterbug” to shame miscreants. Two decades later, a famous TV ad featured a Native American man weeping at the sight of a motorist dumping garbage. “People Start Pollution. People Can Stop It,” was the slogan. The essay in Scientific American, by Matt Wilkins, sees through such charades.

To change the world, we are told to work on ourselves – to change our minds by being more accepting of circumstances

For an actor in neoliberal society, mindfulness is a skill to be cultivated, or a resource to be put to use. When mastered, it helps you to navigate the capitalist ocean’s tricky currents, keeping your attention “present-centred and non-judgmental” to deal with the inevitable stress and anxiety from competition. Mindfulness helps you to maximise your personal wellbeing.

All of this may help you to sleep better at night. But the consequences for society are potentially dire. The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek has analysed this trend. As he sees it, mindfulness is “establishing itself as the hegemonic ideology of global capitalism”, by helping people “to fully participate in the capitalist dynamic while retaining the appearance of mental sanity”.

By deflecting attention from the social structures and material conditions in a capitalist culture, mindfulness is easily co-opted. Celebrity role models bless and endorse it, while Californian companies including Google, Facebook, Twitter, Apple and Zynga have embraced it as an adjunct to their brand. Google’s former in-house mindfulness tsar Chade-Meng Tan had the actual job title Jolly Good Fellow. “Search inside yourself,” he counselled colleagues and readers – for there, not in corporate culture – lies the source of your problems.

The rhetoric of “self-mastery”, “resilience” and “happiness” assumes wellbeing is simply a matter of developing a skill. Mindfulness cheerleaders are particularly fond of this trope, saying we can train our brains to be happy, like exercising muscles. Happiness, freedom and wellbeing become the products of individual effort. Such so-called “skills” can be developed without reliance on external factors, relationships or social conditions. Underneath its therapeutic discourse, mindfulness subtly reframes problems as the outcomes of choices. Personal troubles are never attributed to political or socioeconomic conditions, but are always psychological in nature and diagnosed as pathologies. Society therefore needs therapy, not radical change. This is perhaps why mindfulness initiatives have become so attractive to government policymakers. Societal problems rooted in inequality, racism, poverty, addiction and deteriorating mental health can be reframed in terms of individual psychology, requiring therapeutic help. Vulnerable subjects can even be told to provide this themselves.

Neoliberalism divides the world into winners and losers. It accomplishes this task through its ideological linchpin: the individualisation of all social phenomena. Since the autonomous (and free) individual is the primary focal point for society, social change is achieved not through political protest, organising and collective action, but via the free market and atomised actions of individuals. Any effort to change this through collective structures is generally troublesome to the neoliberal order. It is therefore discouraged.

An illustrative example is the practice of recycling. The real problem is the mass production of plastics by corporations, and their overuse in retail. However, consumers are led to believe that being personally wasteful is the underlying issue, which can be fixed if they change their habits. As a recent essay in Scientific American scoffs: “Recycling plastic is to saving the Earth what hammering a nail is to halting a falling skyscraper.” Yet the neoliberal doctrine of individual responsibility has performed its sleight-of-hand, distracting us from the real culprit. This is far from new. In the 1950s, the “Keep America Beautiful” campaign urged individuals to pick up their trash. The project was bankrolled by corporations such as Coca-Cola, Anheuser-Busch and Phillip Morris, in partnership with the public service announcement Ad Council, which coined the term “litterbug” to shame miscreants. Two decades later, a famous TV ad featured a Native American man weeping at the sight of a motorist dumping garbage. “People Start Pollution. People Can Stop It,” was the slogan. The essay in Scientific American, by Matt Wilkins, sees through such charades.

To change the world, we are told to work on ourselves – to change our minds by being more accepting of circumstances

At face value, these efforts seem benevolent, but they obscure the real problem, which is the role that corporate polluters play in the plastic problem. This clever misdirection has led journalist and author Heather Rogers to describe Keep America Beautiful as the first corporate greenwashing front, as it has helped shift the public focus to consumer recycling behaviour and thwarted legislation that would increase extended producer responsibility for waste management.

We are repeatedly sold the same message: that individual action is the only real way to solve social problems, so we should take responsibility. We are trapped in a neoliberal trance by what the education scholar Henry Giroux calls a “disimagination machine”, because it stifles critical and radical thinking. We are admonished to look inward, and to manage ourselves. Disimagination impels us to abandon creative ideas about new possibilities. Instead of seeking to dismantle capitalism, or rein in its excesses, we should accept its demands and use self-discipline to be more effective in the market. To change the world, we are told to work on ourselves — to change our minds by being more mindful, nonjudgmental, and accepting of circumstances.

It is a fundamental tenet of neoliberal mindfulness, that the source of people’s problems is found in their heads. This has been accentuated by the pathologising and medicalisation of stress, which then requires a remedy and expert treatment – in the form of mindfulness interventions. The ideological message is that if you cannot alter the circumstances causing distress, you can change your reactions to your circumstances. In some ways, this can be helpful, since many things are not in our control. But to abandon all efforts to fix them seems excessive. Mindfulness practices do not permit critique or debate of what might be unjust, culturally toxic or environmentally destructive. Rather, the mindful imperative to “accept things as they are” while practising “nonjudgmental, present moment awareness” acts as a social anesthesia, preserving the status quo.

The mindfulness movement’s promise of “human flourishing” (which is also the rallying cry of positive psychology) is the closest it comes to defining a vision of social change. However, this vision remains individualised and depends on the personal choice to be more mindful. Mindfulness practitioners may of course have a very different political agenda to that of neoliberalism, but the risk is that they start to retreat into their own private worlds and particular identities — which is just where the neoliberal power structures want them.

Mindfulness practice is embedded in what Jennifer Silva calls the “mood economy”. In Coming Up Short: Working-Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty, Silva explains that, like the privatisation of risk, a mood economy makes “individuals solely responsible for their emotional fates”. In such a political economy of affect, emotions are regulated as a means to enhance one’s “emotional capital”. At Google’s Search Inside Yourself mindfulness programme, emotional intelligence (EI) figures prominently in the curriculum. The programme is marketed to Google engineers as instrumental to their career success — by engaging in mindfulness practice, managing emotions generates surplus economic value, equivalent to the acquisition of capital. The mood economy also demands the ability to bounce back from setbacks to stay productive in a precarious economic context. Like positive psychology, the mindfulness movement has merged with the “science of happiness”. Once packaged in this way, it can be sold as a technique for personal life-hacking optimisation, disembedding individuals from social worlds.

We are repeatedly sold the same message: that individual action is the only real way to solve social problems, so we should take responsibility. We are trapped in a neoliberal trance by what the education scholar Henry Giroux calls a “disimagination machine”, because it stifles critical and radical thinking. We are admonished to look inward, and to manage ourselves. Disimagination impels us to abandon creative ideas about new possibilities. Instead of seeking to dismantle capitalism, or rein in its excesses, we should accept its demands and use self-discipline to be more effective in the market. To change the world, we are told to work on ourselves — to change our minds by being more mindful, nonjudgmental, and accepting of circumstances.

It is a fundamental tenet of neoliberal mindfulness, that the source of people’s problems is found in their heads. This has been accentuated by the pathologising and medicalisation of stress, which then requires a remedy and expert treatment – in the form of mindfulness interventions. The ideological message is that if you cannot alter the circumstances causing distress, you can change your reactions to your circumstances. In some ways, this can be helpful, since many things are not in our control. But to abandon all efforts to fix them seems excessive. Mindfulness practices do not permit critique or debate of what might be unjust, culturally toxic or environmentally destructive. Rather, the mindful imperative to “accept things as they are” while practising “nonjudgmental, present moment awareness” acts as a social anesthesia, preserving the status quo.

The mindfulness movement’s promise of “human flourishing” (which is also the rallying cry of positive psychology) is the closest it comes to defining a vision of social change. However, this vision remains individualised and depends on the personal choice to be more mindful. Mindfulness practitioners may of course have a very different political agenda to that of neoliberalism, but the risk is that they start to retreat into their own private worlds and particular identities — which is just where the neoliberal power structures want them.

Mindfulness practice is embedded in what Jennifer Silva calls the “mood economy”. In Coming Up Short: Working-Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty, Silva explains that, like the privatisation of risk, a mood economy makes “individuals solely responsible for their emotional fates”. In such a political economy of affect, emotions are regulated as a means to enhance one’s “emotional capital”. At Google’s Search Inside Yourself mindfulness programme, emotional intelligence (EI) figures prominently in the curriculum. The programme is marketed to Google engineers as instrumental to their career success — by engaging in mindfulness practice, managing emotions generates surplus economic value, equivalent to the acquisition of capital. The mood economy also demands the ability to bounce back from setbacks to stay productive in a precarious economic context. Like positive psychology, the mindfulness movement has merged with the “science of happiness”. Once packaged in this way, it can be sold as a technique for personal life-hacking optimisation, disembedding individuals from social worlds.

From inboxing to thought showers: how business bullshit took over

All the promises of mindfulness resonate with what the University of Chicago cultural theorist Lauren Berlant calls “cruel optimism”, a defining neoliberal characteristic. It is cruel in that one makes affective investments in what amount to fantasies. We are told that if we practice mindfulness, and get our individual lives in order, we can be happy and secure. It is therefore implied that stable employment, home ownership, social mobility, career success and equality will naturally follow. We are also promised that we can gain self-mastery, controlling our minds and emotions so we can thrive and flourish amid the vagaries of capitalism.As Joshua Eisen, the author of Mindful Calculations, puts it: “Like kale, acai berries, gym memberships, vitamin water, and other new year’s resolutions, mindfulness indexes a profound desire to change, but one premised on a fundamental reassertion of neoliberal fantasies of self-control and unfettered agency.” We just have to sit in silence, watching our breath, and wait. It is doubly cruel because these normative fantasies of the “good life” are already crumbling under neoliberalism, and we make it worse if we focus individually on our feelings. Neglecting shared vulnerabilities and interdependence, we disimagine the collective ways we might protect ourselves. And despite the emptiness of nurturing fantasies, we continue to cling to them.

Mindfulness isn’t cruel in and of itself. It’s only cruel when fetishised and attached to inflated promises. It is then, as Berlant points out, that “the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially”. The cruelty lies in supporting the status quo while using the language of transformation. This is how neoliberal mindfulness promotes an individualistic vision of human flourishing, enticing us to accept things as they are, mindfully enduring the ravages of capitalism.

Tuesday 8 January 2019

Saturday 2 June 2018

Using Visualisation to improve your cricket

Tim Wigmore in Cricinfo

It was the night before the final day of West Indies' Test against Australia in Barbados in 1999. West Indies were in jeopardy: 85 for 3, in pursuit of 308 to win. Prospects of victory, it was obvious, hinged upon Brian Lara, who was 2 not out, after surviving a tetchy end to the fourth day.

When stumps were called, Lara had a chat with Rudi Webster, West Indies' mental-skills coach. In his book, Think Like A Champion, Webster recalls:

"My advice to him was to imagine the game as already won and to visualise and feel himself constructing that victory. I asked him to mentally rehearse seeing the ball the moment it leaves the bowler's hand and to feel his movements as he gets into position smoothly and quickly to stroke the ball into the gaps in the field. I also asked him to see and feel himself playing his natural game, facing one ball at a time, and enjoying the challenge."

The following day, Lara played one of the greatest innings of all time. In the euphoria after his 153 not out, Lara told Webster: "I was seeing the ball so clearly that I couldn't miss it. Everything worked out the way I imagined it."

Lara was an adherent of visualisation, as Rahul Bhattacharya detailed for the Cricket Monthly. An old school friend, Nicholas Gomez, had earlier given him a book on Michael Jordan, which included a section on how Jordan used visualisation. At 6am on the day of his 153 not out, Lara called Gomez. "We went about planning this innings against the best team in the world. And it was amazing to see how it just came to fruition."

Before they head onto the field for a game, most of the world's best cricketers have already, like Lara, been there in their heads. Some do this in the middle itself - either with their bat or just their hands; some just do it in front of a mirror at home or, as Lara did, through talking the innings over.

Such visualisation aims to prepare players by decoding the opposition and conditions before game day. "What you're trying to do in visualisation is build that depth of experience even though you're not physically doing it," explains Jeremy Snape, a former England cricketer who has worked as a sports psychologist in six editions of the IPL. "When your brain has that conditioning, it's more likely to respond in a favourable way under pressure. What athletes then do is try and first visualise it, then stimulate it, then practise it, then do it."

Visualisation can help players remain more grounded during matches, keeping their focus upon their normal processes rather than what is new. Snape explains: "We want to make sure that our decision-making is as calm and rational as it possibly can be, rather than being emotional and irrational, which is what happens under pressure."

It was the night before the final day of West Indies' Test against Australia in Barbados in 1999. West Indies were in jeopardy: 85 for 3, in pursuit of 308 to win. Prospects of victory, it was obvious, hinged upon Brian Lara, who was 2 not out, after surviving a tetchy end to the fourth day.

When stumps were called, Lara had a chat with Rudi Webster, West Indies' mental-skills coach. In his book, Think Like A Champion, Webster recalls:

"My advice to him was to imagine the game as already won and to visualise and feel himself constructing that victory. I asked him to mentally rehearse seeing the ball the moment it leaves the bowler's hand and to feel his movements as he gets into position smoothly and quickly to stroke the ball into the gaps in the field. I also asked him to see and feel himself playing his natural game, facing one ball at a time, and enjoying the challenge."

The following day, Lara played one of the greatest innings of all time. In the euphoria after his 153 not out, Lara told Webster: "I was seeing the ball so clearly that I couldn't miss it. Everything worked out the way I imagined it."

Lara was an adherent of visualisation, as Rahul Bhattacharya detailed for the Cricket Monthly. An old school friend, Nicholas Gomez, had earlier given him a book on Michael Jordan, which included a section on how Jordan used visualisation. At 6am on the day of his 153 not out, Lara called Gomez. "We went about planning this innings against the best team in the world. And it was amazing to see how it just came to fruition."

Before they head onto the field for a game, most of the world's best cricketers have already, like Lara, been there in their heads. Some do this in the middle itself - either with their bat or just their hands; some just do it in front of a mirror at home or, as Lara did, through talking the innings over.

Such visualisation aims to prepare players by decoding the opposition and conditions before game day. "What you're trying to do in visualisation is build that depth of experience even though you're not physically doing it," explains Jeremy Snape, a former England cricketer who has worked as a sports psychologist in six editions of the IPL. "When your brain has that conditioning, it's more likely to respond in a favourable way under pressure. What athletes then do is try and first visualise it, then stimulate it, then practise it, then do it."

Visualisation can help players remain more grounded during matches, keeping their focus upon their normal processes rather than what is new. Snape explains: "We want to make sure that our decision-making is as calm and rational as it possibly can be, rather than being emotional and irrational, which is what happens under pressure."

Matthew Hayden would habitually sit and meditate on the pitch a day before the match © Getty Images

The tool can be invaluable for players who don't expect to play. On South Africa's tour of Australia in 2008, JP Duminy was the reserve batsman and faced a tour carrying drinks. Snape, then a consulting psychologist for South Africa, observed that Duminy seemed "disgruntled, dragging around his bag at training". He set Duminy a challenge: "Why don't you prepare for this Test match as if you're the captain of South Africa in four years' time? We prepared as if he was going to take them on for real." Duminy was given various simulations, including imagining that he was facing Mitchell Johnson when Lonwabo Tsotsobe bowled his left-arm pace in the nets.

The day before the first Test, Ashwell Prince broke his thumb and was ruled out on the morning of the game. Duminy hit 50 not out in the second innings as South Africa chased down 414 in Perth. In the next Test he hit 166, an innings for the ages, as South Africa sealed their first Test series victory in Australia.

Pre-game visualisation aims not to inhibit instinctive play but to enable it. After each net session the day before a game, Matthew Hayden sat cross-legged by the stumps, grasping his bat in his hands and closing his eyes. He began the process as a child when he would train until he dropped, and then sit down to discuss the session with his older brother, who was his coach.

Of his method throughout his professional career, Hayden explained: "I continued the process of gathering my thoughts, sitting down in an environment which was comfortable and going through the kind of expectations I had in store for me in the week's period of the Test or the one-dayers, getting used to the conditions, understanding where the breeze is coming from, what the bowler's arms were going to look like, so that there were no surprises on the day, and just going through how I felt at that time."

After playing the innings in his head - not just picturing the bowlers he would face, but their angles of attack and how they would try to bowl to him - Hayden returned the next day to bat. "In the middle, I would let it all go and be completely relaxed, looking down at the wicket, loving the environment of being outside and being in a physical state of mind where I would be at peace."

Players even visualise how best to breathe between balls - which can help them maintain their equanimity and focus, and so keep their focus on the next delivery, rather than the opposition's attempts to frazzle them. For instance, when a bowler moves several fielders back, as preparation to bowl a bouncer, Snape says, earlier visualisation of breathing techniques can keep batsmen calm in the moment - and make them less susceptible to bowlers bowling a yorker as a bluff.

For batsmen, visualisation is a tool to demystify bowlers. On West Indies' tour of Australia in 1975-76 tour, Alvin Kallicharran was struggling against Jeff Thomson. Webster encouraged Kallicharran to practise against Thomson in slow motion, and then imagine that he was bowling at his normal speed. When he became comfortable with the idea of this, Kallicharran then visualised facing Thomson at twice his normal speed - and, in his mind, could still see the ball when it was released from the hand, gauge the line, angle and length and get into position to play his shots.

In his next innings, Kallicharran made a rapid 76. He then told Webster: "Everything happened the way we visualised them. I was alert but relaxed throughout my innings, and at no stage did I lose control. And I saw the big, bright red ball the moment it left the bowler's hand."

While visualisation is particularly favoured by batsmen, some bowlers have also used it to good effect. Wasim Akram's late wife, Huma, a psychologist and psychotherapist, introduced him to the concept.

© ESPNcricinfo Ltd

© ESPNcricinfo Ltd

"When I started playing cricket as a professional, nobody told me how important the mind was in cricket," he said. During matches, Akram "used to visualise most of the deliveries that I bowled. For example, if there were reverse swing, I would bowl three awayswingers and then the inswinger. But before I bowled the inswinger I would visualise it and would see the ball swinging from outside the off stump into the batsman's pads or the stumps."

As with many other areas beyond the field of play, more cash and personnel are now being allocated to sports psychology.

"The understanding of neuroscience is the thing that's advanced in the last five-ten years," Snape observes. "Neuroplasticity - the ability of the brain to grow connections and change through repetition and skill development - is really powerful." In Formula One, drivers can now visualise their lap times to within a few seconds, such is their depth of preparation.

Virtual-reality technology, which is already functional and rapidly developing, will take visualisation to a new level. Players will not just be able to visualise the bowlers but also the grounds, crowd and the noise in a stadium. It will then be possible for overseas batsmen to prepare for a tour of England, long before they have even left for the trip, by strapping on VR goggles and facing James Anderson and Stuart Broad at Lord's and Trent Bridge.

Not even Lara before Bridgetown was able to prepare for an innings with such thoroughness. But visualising like Lara is one thing; batting like him quite another.

The tool can be invaluable for players who don't expect to play. On South Africa's tour of Australia in 2008, JP Duminy was the reserve batsman and faced a tour carrying drinks. Snape, then a consulting psychologist for South Africa, observed that Duminy seemed "disgruntled, dragging around his bag at training". He set Duminy a challenge: "Why don't you prepare for this Test match as if you're the captain of South Africa in four years' time? We prepared as if he was going to take them on for real." Duminy was given various simulations, including imagining that he was facing Mitchell Johnson when Lonwabo Tsotsobe bowled his left-arm pace in the nets.

The day before the first Test, Ashwell Prince broke his thumb and was ruled out on the morning of the game. Duminy hit 50 not out in the second innings as South Africa chased down 414 in Perth. In the next Test he hit 166, an innings for the ages, as South Africa sealed their first Test series victory in Australia.

Pre-game visualisation aims not to inhibit instinctive play but to enable it. After each net session the day before a game, Matthew Hayden sat cross-legged by the stumps, grasping his bat in his hands and closing his eyes. He began the process as a child when he would train until he dropped, and then sit down to discuss the session with his older brother, who was his coach.

Of his method throughout his professional career, Hayden explained: "I continued the process of gathering my thoughts, sitting down in an environment which was comfortable and going through the kind of expectations I had in store for me in the week's period of the Test or the one-dayers, getting used to the conditions, understanding where the breeze is coming from, what the bowler's arms were going to look like, so that there were no surprises on the day, and just going through how I felt at that time."

After playing the innings in his head - not just picturing the bowlers he would face, but their angles of attack and how they would try to bowl to him - Hayden returned the next day to bat. "In the middle, I would let it all go and be completely relaxed, looking down at the wicket, loving the environment of being outside and being in a physical state of mind where I would be at peace."

Players even visualise how best to breathe between balls - which can help them maintain their equanimity and focus, and so keep their focus on the next delivery, rather than the opposition's attempts to frazzle them. For instance, when a bowler moves several fielders back, as preparation to bowl a bouncer, Snape says, earlier visualisation of breathing techniques can keep batsmen calm in the moment - and make them less susceptible to bowlers bowling a yorker as a bluff.

For batsmen, visualisation is a tool to demystify bowlers. On West Indies' tour of Australia in 1975-76 tour, Alvin Kallicharran was struggling against Jeff Thomson. Webster encouraged Kallicharran to practise against Thomson in slow motion, and then imagine that he was bowling at his normal speed. When he became comfortable with the idea of this, Kallicharran then visualised facing Thomson at twice his normal speed - and, in his mind, could still see the ball when it was released from the hand, gauge the line, angle and length and get into position to play his shots.

In his next innings, Kallicharran made a rapid 76. He then told Webster: "Everything happened the way we visualised them. I was alert but relaxed throughout my innings, and at no stage did I lose control. And I saw the big, bright red ball the moment it left the bowler's hand."

While visualisation is particularly favoured by batsmen, some bowlers have also used it to good effect. Wasim Akram's late wife, Huma, a psychologist and psychotherapist, introduced him to the concept.

© ESPNcricinfo Ltd

© ESPNcricinfo Ltd"When I started playing cricket as a professional, nobody told me how important the mind was in cricket," he said. During matches, Akram "used to visualise most of the deliveries that I bowled. For example, if there were reverse swing, I would bowl three awayswingers and then the inswinger. But before I bowled the inswinger I would visualise it and would see the ball swinging from outside the off stump into the batsman's pads or the stumps."

As with many other areas beyond the field of play, more cash and personnel are now being allocated to sports psychology.

"The understanding of neuroscience is the thing that's advanced in the last five-ten years," Snape observes. "Neuroplasticity - the ability of the brain to grow connections and change through repetition and skill development - is really powerful." In Formula One, drivers can now visualise their lap times to within a few seconds, such is their depth of preparation.

Virtual-reality technology, which is already functional and rapidly developing, will take visualisation to a new level. Players will not just be able to visualise the bowlers but also the grounds, crowd and the noise in a stadium. It will then be possible for overseas batsmen to prepare for a tour of England, long before they have even left for the trip, by strapping on VR goggles and facing James Anderson and Stuart Broad at Lord's and Trent Bridge.

Not even Lara before Bridgetown was able to prepare for an innings with such thoroughness. But visualising like Lara is one thing; batting like him quite another.

Saturday 6 January 2018

Cleaning is a good meditation practice

Shoukei Matsumoto in The Guardian

Mental health counsellors often recommend that clients clean their home environments every day. Dirt and squalor can be symptoms of unhappiness or illness. But cleanliness is not only about mental health. It is the most basic practice that all forms of Japanese Buddhism have in common. In Japanese Buddhism, it is said that what you must do in the pursuit of your spirituality is clean, clean, clean. This is because the practice of cleaning is powerful.

Of course, as a monk who is dedicated to spiritual life, I recommend Buddhist concepts and practices. But you don’t have to convert to a new religion to learn from it. Many people’s associations with the word “religion” may include a set of rules to regulate people’s values and actions; the creation of an irrational transcendent entity; or the idea of a crutch for people who cannot think for themselves. In my view, though, a respectable religion does not exist to bind one’s values or actions. It is there to free people from the systems and standards that order society. In Japanese characters, the word “freedom” is written as “caused by oneself”.

Cleaning practice is not a tool but a purpose in itself

Cleaning practice, by which I mean the routines whereby we sweep, wipe, polish, wash and tidy, is one step on this path towards inner peace. In Japanese Buddhism, we don’t separate a self from its environment, and cleaning expresses our respect for and sense of wholeness with the world that surrounds us.

You can see the presence of nature in the Japanese traditions of sado (tea ceremonies) or kado (flower arranging), which were both originally born from Buddhism. But the idea of “nature” in Japan has been strongly influenced by western culture. Pronounced “shizen”, the characters reflect a human-centred version of the world in which humans stand at the top of a hierarchy as the agent or messenger of the creator.

But there is another sense of “nature” derived from ancient Japanese. Pronounced “jinen”, the same characters once meant “let it go” or “it is as it is” – a definition much closer to Buddhist philosophy, with its links to animism and the worship of nature.

After Buddhism and the other philosophies were introduced to the Japanese people, they began to see nature not only in humans, but also in all sentient beings, and even in mountains, rivers, plants and trees. This view of nature persists in modern Japanese culture – for example in Pokémon’s characters or Studio Ghibli films such as Arrietty, with their environmentalist messages. As a result, even when we pronounce the characters for nature as “shizen”, the term still carries with it the Japanese idea that humans are not excluded from nature, but are part of it.

Buddhism says the notion that you have your own personality is an illusion that your ego creates – and cleaning is a means to let go of this. The characters for “human being” in Japanese mean “person” and “between”. Human being is “a person in between”. Thus, you as a human being only exist through your relations with others – people such as friends, colleagues and family. You as a person have some particular words, facial expressions and behaviours, but these arise only through your interaction and connections with other people. This is the Buddhist concept “en” or interdependence.

Buddhist cleaning practice provides each of us with an opportunity to understand this concept. You don’t have to acquire special techniques, hire a professional cleaning consultant, or perform the special rituals used by senior monks.

The basics are very simple. Sweep from the top to the bottom of your home, wipe along the stream of objects and handle everything with care. After you start cleaning your home, you can extend cleaning practice to other things, including your body. How you can apply cleaning practice to your mind is a question I want to leave unanswered, but if you practise cleaning, cleaning and more cleaning, you will eventually know that you have been cleaning your inner world along with the outer one.

Of course Japanese temples sometimes employ cleaners when they are short of hands. But Buddhist monks also clean by themselves. This is because the cleaning practice is not a tool but a purpose in itself. Would you outsource your meditation practice to others?

As with meditation practice, there is no endpoint of the cleaning practice. Right after I am satisfied with the cleanliness of the garden I have swept, fallen leaves and dust begin to accumulate. Similarly, right after I feel peaceful with my ego-less mindfulness, anger or anxiety begin once again to emerge in my mind. The ego endlessly arises in my mind, so I keep cleaning for my inner peace. No cleaning, no life.

Mental health counsellors often recommend that clients clean their home environments every day. Dirt and squalor can be symptoms of unhappiness or illness. But cleanliness is not only about mental health. It is the most basic practice that all forms of Japanese Buddhism have in common. In Japanese Buddhism, it is said that what you must do in the pursuit of your spirituality is clean, clean, clean. This is because the practice of cleaning is powerful.

Of course, as a monk who is dedicated to spiritual life, I recommend Buddhist concepts and practices. But you don’t have to convert to a new religion to learn from it. Many people’s associations with the word “religion” may include a set of rules to regulate people’s values and actions; the creation of an irrational transcendent entity; or the idea of a crutch for people who cannot think for themselves. In my view, though, a respectable religion does not exist to bind one’s values or actions. It is there to free people from the systems and standards that order society. In Japanese characters, the word “freedom” is written as “caused by oneself”.

Cleaning practice is not a tool but a purpose in itself

Cleaning practice, by which I mean the routines whereby we sweep, wipe, polish, wash and tidy, is one step on this path towards inner peace. In Japanese Buddhism, we don’t separate a self from its environment, and cleaning expresses our respect for and sense of wholeness with the world that surrounds us.

You can see the presence of nature in the Japanese traditions of sado (tea ceremonies) or kado (flower arranging), which were both originally born from Buddhism. But the idea of “nature” in Japan has been strongly influenced by western culture. Pronounced “shizen”, the characters reflect a human-centred version of the world in which humans stand at the top of a hierarchy as the agent or messenger of the creator.

But there is another sense of “nature” derived from ancient Japanese. Pronounced “jinen”, the same characters once meant “let it go” or “it is as it is” – a definition much closer to Buddhist philosophy, with its links to animism and the worship of nature.

After Buddhism and the other philosophies were introduced to the Japanese people, they began to see nature not only in humans, but also in all sentient beings, and even in mountains, rivers, plants and trees. This view of nature persists in modern Japanese culture – for example in Pokémon’s characters or Studio Ghibli films such as Arrietty, with their environmentalist messages. As a result, even when we pronounce the characters for nature as “shizen”, the term still carries with it the Japanese idea that humans are not excluded from nature, but are part of it.

Buddhism says the notion that you have your own personality is an illusion that your ego creates – and cleaning is a means to let go of this. The characters for “human being” in Japanese mean “person” and “between”. Human being is “a person in between”. Thus, you as a human being only exist through your relations with others – people such as friends, colleagues and family. You as a person have some particular words, facial expressions and behaviours, but these arise only through your interaction and connections with other people. This is the Buddhist concept “en” or interdependence.

Buddhist cleaning practice provides each of us with an opportunity to understand this concept. You don’t have to acquire special techniques, hire a professional cleaning consultant, or perform the special rituals used by senior monks.